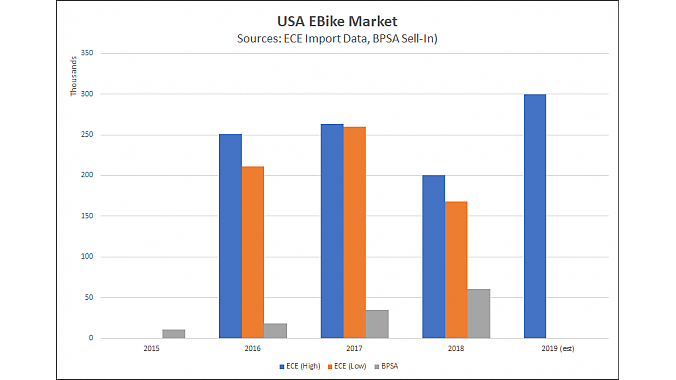

In part one of this series, we discussed a core reality facing the IBD channel in the e-bike market. Although its share of market is growing, IBD brands still only represent a 25-30 percent of e-bike unit sales in the USA, depending on whose numbers you use. The ones shown here are from the BPSA’s sell-in data and the consulting group eCycleElectric (ECE), respectively.

The other 70-75 percent of the market represents some 120-150 active e-bike brands, according to ECE managing director Ed Benjamin. Market share is further broken down into consumer-direct brands (including e-bikes from car companies and bikeshare providers) and an emergent independent sector, which I’ve labeled the EBD (as opposed to the e-bike sector of the traditional IBD, or EIBD).

It’s the EBD niche I want to unpack in this installment, both because it provides the most direct competition for traditional IBD brands and dealers, and because it offers the greatest opportunities for synergy as well. But part of the challenge is that no one, not even e-bike industry insiders I talked to, have any idea how many of these EBD businesses there are. There’s a lot of volatility in the space, they agree, with EBDs continuously popping in and out of existence like quantum particles, and about as predictably.

So, who's number one?

At the BPSA/PeopleForBikes E-Bike summit in February, a data capture report from The NPD Group showed the leading EIBD brands as Trek, Specialized, Electra, Raleigh and Giant, in that order. This is a major shift from 2015, when the leaders were Stromer, Raleigh, Specialized, Haibike and Trek. Clearly the balance of power is still very much in flux.

On the EBD/Direct side of the business, Benjamin is reluctant to discuss details, although he agrees major players include Pedego and Rad Power. Overall, he says, the EIBD and EBD markets are about equal in size, while the consumer-direct segment controls about half of all units, but significantly less in terms of dollars. Traditional mass market stores like Walmart aren’t even on the radar screen, he says, and few of the large sporting brands. And that spells opportunity for brick-and-mortar retailers of all persuasions.

There’s a little fudge factor in these numbers, since some primarily direct brands are also sold by EBD and even EIBD retailers. But the bottom line is: the traditional designations of independent, sporting and mass channels are breaking down, and nowhere is this more apparent than in the booming e-bike market.

Of the main non-IBD brands Benjamin tags as industry leaders, Rad Power is entirely consumer-direct, aside from the sales floor at its Seattle headquarters building. And then there’s Pedego, which has a sales model all its own. Two of them, actually.

“One of the things that's made us so successful is we don't have the bicycle industry mentality. I come from the auto industry, and we brought that model to the e-bike business. It's not necessarily better, it's just different, but it works for us,” said Pedego founder and CEO Don DiCostanzo.

It’s obvious DiCostanzo has given this speech a time or two before, but it hasn’t damped his enthusiasm. As he says, the Pedego retailer model is based on the automobile dealership: an independent retailer 100 percent devoted to the Pedego brand. In exchange for that exclusivity, he explains, Pedego retailers have a protected-by-contract exclusive sales area and enjoy sales and marketing support beyond what IBD brands traditionally provide.

The traditional designations of independent, sporting and mass channels are breaking down, and nowhere is this more apparent than in the booming e-bike market.

Business is good, DiCostanzo claims, and getting better. “We currently have 108 Pedego retailers in the U.S. and Canada, including five or six opened since the first of the year. (That includes) two regular IBD retailers who’ve opened separate Pedego locations, and eight locations we own outright. We anticipate growing (the total) to about 150 in 2019.”

There’s another piece of the Pedego puzzle starting to fall into place, too. A hybrid retail model, a dedicated Pedego store-within-a-store concept, targeted at traditional IBDs who are willing to make Pedego their exclusive e-bike line. "We have applications from 15 retailers, currently signed three, working for a total of 10 in 2019 as proof of concept,” DiCostanzo says. “After that, we’ll see how it goes.”

“We did $50 million out of 108 stores last year with zero store failures,” he concludes, “and that makes us bigger (in e-bike sales) than Trek. Maybe not Trek and Electra together, but certainly bigger than Trek.”

“One of the things that's made us so successful is we don't have the bicycle industry mentality." — Don DiCostanzo.

Since Trek doesn’t publish sales numbers, there’s no way to determine the accuracy of this statement. But $50 million in e-bike sales from a single brand is nothing to sneeze at, either. As a bench mark, recall that we mentioned in Part One that the NPD Group estimates retail e-bike sales, through all the channels it measures, at $143 million for 2018.

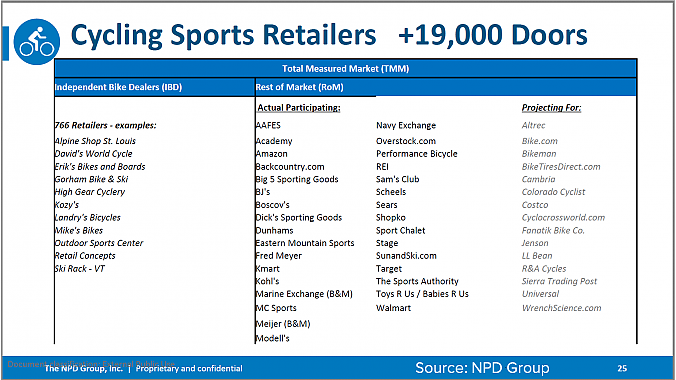

Once again, we need to be clear about what’s being measured. NPD’s $143 million estimate includes retail dollar sell-through from participating retailers, sporting channels including Dick’s and REI, selected consumer-direct companies, and Amazon Direct (although not third-party retailers on Amazon). More to the point, it specifically does not measure sales in the EBD channel, including Pedego’s. Here’s the complete explanation from the BPSA/People For Bikes E-Bike Summit last month (note that although it’s labeled confidential, the slide is also labeled for “External Public Use”).

When cycling cultures — and products and brands and channels — collide.

I’ll unpack all this in more detail in the final part of this series, which is scheduled to go live Monday, April 11. But for the time being, I’d like to focus on a single question: Will the e-bike ultimately become an integrated part of the traditional bike business (as mountain bikes have done), or is it sufficiently different that it will become its own semi-independent channel (as with BMX or triathlon)?

Let’s start with DiCostanzo:

“People who buy Trek bikes do it because they're Trek customers and their family all rides Trek. But among potential e-bike customers coming into our stores, they don't even recognize the name. And if they do, they don't associate it with e-bikes. (…) At the end of the day, bikes are all commodities, and the differentiator is how the experience is delivered to the customer and the support the brand gets from the home office.”

On the other hand, this is a man who’s launching a project to seed his product into traditional bike shops, so it sounds like Pedego’s founder is in the semi-independent camp.

I also spoke with Noel Kegel, president of the Wheel & Sprocket group of stores in Wisconsin and Illinois. W & S has 10 locations, including what its website describes as an “E-Bike Superstore." Kegel is a thoughtful guy, and he articulates his experience clearly.

"The e-bike superstore was an experiment,” he says. “We separated it with a separate entrance, separate sign, separate manager, and separate marketing, sort of making it a different store. Though it was in the adjoining space in the strip mall to our regular store, and had a pass-through to it, the experiment was to see if there was a different customer and a different experience that we could tap into.

“In five years, 10 years, they'll come in saying 'I'm looking for a bike' and they'll mean an e-bike."— Noel Kegel.

“After one season experimenting, we’ve concluded to discontinue the stand-alone e-bike store. What we learned talking to customers and in focus groups was that the Wheel & Sprocket brand was primary to the e-bike portion. Most of the people coming into the e-bike store said they were coming in looking exclusively for an e-bike. But when we measured the stand-alone's sales against our Appleton store, a high-performing traditional location with a significant e-bike inventory, the mixed environment performed every bit as well.

“In five years, 10 years, they'll come in saying 'I'm looking for a bike' and they'll mean an e-bike. The hard line between e-bikes and traditional bikes is blurring quickly — this will no longer be a niche. I suspect that might be challenging for the e-bike only shops of the world, where customers can only get that product and not all the other parts, accessories and service that go with it. Or maybe the family comes in and the mom is interested in an e-bike and the dad wants a road bike and the kids want something else.”

So Kegel seems firmly in the “one happy family” contingent. But perhaps by virtue of its size, his Wheel & Sprocket stores enjoy an advantage the enormous majority of traditional bike shops don’t: they can be very selective which brands are represented on the floor. Currently, Kegel explains, his stores carry e-bikes from Trek, Riese & Müller, Felt, Tern, iZip and Yuba.

Finally, I put the same question to NBDA president Brandee Lepak. Here’s her take:

“As an association, we need to take a pause and think about what really helps our IBDs sell as many bikes as possible. And of course the same goes for EBDs too. We'd love to have EBD stores join the NBDA because we all learn from one another when we share best practices. I've seen an incredible opportunity for us in our own retail business (with e-bikes) and I'd like other retailers to have that opportunity, too."

Three industry leaders, three different views of where all this is heading for the traditional IBD channel.

But the upshot is not just that the e-bike is here to stay and represents a large and fast-growing opportunity. It’s not even about IEBD vs EBD vs mass or direct. The big picture here is that the e-bike has the power to disrupt the traditional bicycle business at every level and across all markets, just as surely as the mountain bike did in the ‘80s and the drop-bar 10-speed did 20 years before that.

And that’s what we’re going to talk about in part three.