A number of readers (you know who you are) took exception to last month’s description of suppliers’ COVID-era over-ordering as “adolescent.” For the record, my exact words were, "Now it’s halfway through 2025 and suppliers are still — still! — choking on industry-record levels of inventory, five years after behaving like a bunch of drunken adolescents at an all-night kegger."

Those words were absolutely over the top and deliberately chosen to be that way in order to caricaturize suppliers’ behavior at the time. But the real question is whether suppliers were actually forced into that harrowing situation by factors beyond their control or simply reacted, well, adolescently.

As retired pro road racer and respected industry watcher Wayne Stetina put it in a LinkedIn comment in response to my piece, “Rather than reckless-drunken/teenager-behavior, I would offer a more rational explanation why the entire bike industry went off the rails. When each retailer was getting allocated a fraction of inventory they initially needed during due to temporarily increased Pandemic consumer demand + supply chain disruptions, each retailer deliberately inflated their orders with every supplier hoping to get a few more bikes, P&A."

“This short term order inflation from individual SBR’s was rational behavior,” Stetina continued, “compounding [that] with every supplier resulted in a crushing inventory surplus across the board. For the better part of a year the largest warehouse of every supplier was stuck in container ships unable to unload at ports."

Stetina went on to say, “The bike industry has no aggregate worldwide factory output visibility v total worldwide consumer demand (or sell thru). That seems as much a pipe dream to rationalize industry-wide forecasting that could prevent the post-Pandemic inventory train wreck as keystone margins in the age of D2C brand proliferation.”

My response was that the scenario Stetina described is what economists call The Bullwhip Effect, first brought to bike industry attention by industry Cassandra Jay Townley and described by me in BRAIN back in November of 2022.

Previously, Brose Group OE sales manager and industry member Dan Jeffris had replied to Stetina thusly:

“I don't believe that IBD ordering was a root cause,” Jeffris said in the same LinkedIn thread. “If, as you say, suppliers took those inflated customer orders on face value, then they were either lazy and lacking fundamental business acumen (unlikely) or greedy (likely). Every supplier should analyze customer orders before accepting or confirming them by examining order history and forecasts, current trends and potential outcomes (stress test your assumptions vs. your businesses fundamentals). But then, it seems the entire supply chain system broke down for a minute, along with rational thought, and here we are. Still.”

Finally, I chimed in, “Granting myself a little editorial liberty with the ‘drunken adolescents’ line (it's actually lifted from the ‘intergalactic kegger’ quote in the original Men In Black), no one is responsible for the hugely inflated orders suppliers placed with their factories other than the suppliers themselves.

“It's called Due Diligence for a reason,” I added.

Finally, I noted that (Stetina’s) former employer, Shimano, “became The Adult In The Room who refused to go along with the ‘all the other kids were doing it’ Bullwhip hysteria, and emerged from the post-COVID inventory carnage relatively unscathed.”

I’ll quote Stetina at more length about that last bit in next month’s installation. Meanwhile, you can read the entire LinkedIn exchange here and decide for yourself.

For purposes of this piece, I would go even further with my comments about suppliers’ allegedly adolescent behavior. As my wife and I continue to impress on our 13-year-old granddaughter, whom we are raising, the difference between adults and children — in fact, the literal definition of that difference — is that adults take responsibility for their actions, and for the consequences of those actions.

Anybody here see a single member of The Quadrumvirate stepping up and acknowledging their role in the current industry inventory SNAFU, which continues to impact everyone in the supply chain on a daily basis?

Didn’t think so.

But wait a minute, I hear you say. Didn’t the entire Bullwhip start with dealers placing inflated orders, not suppliers?

Yes it absolutely did. But there’s several things about that.

Dealers have always over-ordered product they think will be in high demand or short supply. Suppliers aren’t dumb. They know this: “Order 20 to get 10.” But instead of accounting for dealer inflation and adjusting accordingly, they upped their own factory orders over and above the inflated dealer demand. And before they did so, they applied two additional kinds of pressure (some dealers I know have actually used the words “coercion” or “extortion”) on retailers to get them to increase their orders even further.

The first is a familiar ploy, where the dealer orders 20 expecting to get 10, but then the rep offers a naked threat: “You know, demand is so high you better order 50 or you won’t get any at all.”

Fear Of Missing Out is a powerful motivator. And the supplier business strategy, which is predicated on moving more units (as opposed to, y’know, maximizing profits, but more about this next month) is all about FOMO.

The second form of pressure is unique to Bike 4.0, although an earlier version was common as dirt in the 3.0 era. Back then, it was the naked threat of opening additional dealers in the market. Nowadays, it tends to be more insidious, something like, “Nice shop you got here. Be a shame if anything happened to it. You know, like a company store opening up across the street or something.”

The bigger — and even uglier — picture

“The bicycle industry is not in transition as many insiders suggest; it is merely the next phase of the bullwhip.” — Jeroen Both, former chief supply chain officer at Accell Group, quoted in Bike Europe, June 10, 2025.

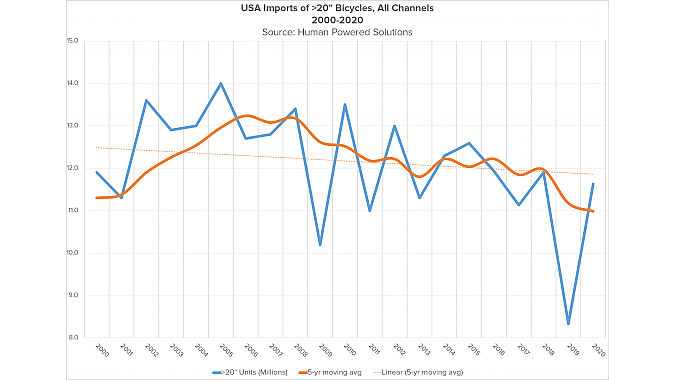

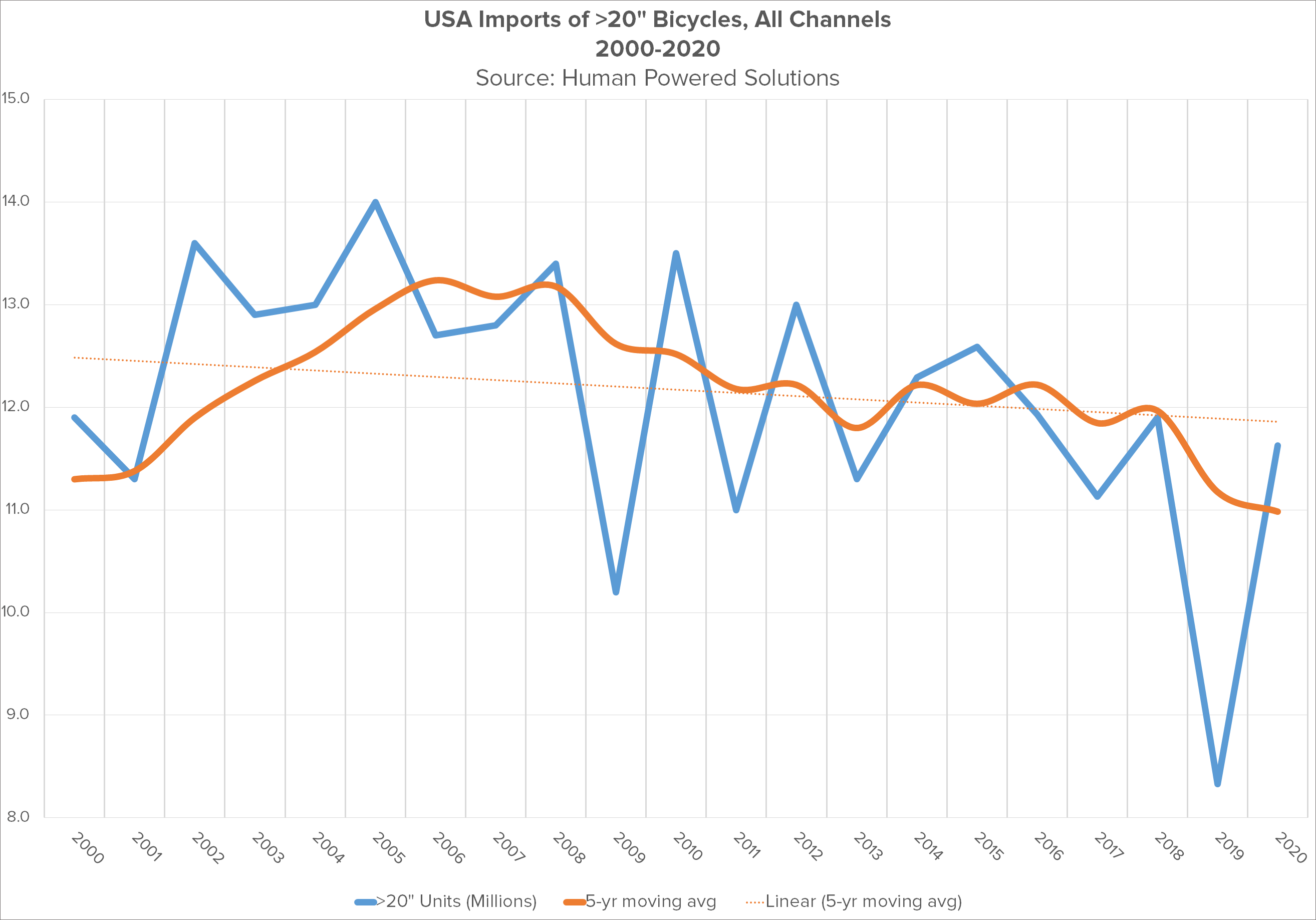

To my larger point, the U.S. bike industry has been plagued with oversupply not just post-COVID, but throughout the entire current millennium. In fact, we've had in-season discounting of excess inventory virtually every single year since 2000, with the Great Recession of 2009 and the anomalous 2019 seasons offering the only exceptions.

We are an industry that shoots itself in the foot year after year in terms of profitability; it’s literally baked into our channel-wide business model. In fact, we metaphorically shoot that foot all the way off, leaving ourselves with no firm foundation to stand on. (And the practice of model years only makes it worse, too, but I’ve already written about that more than a decade ago, here and here.)

Taken together, if those aren't signs of a dysfunctional industry, I'd like to know what are.

As long as I’m quoting myself, here’s part of an exchange I had with a Group member in the Facebook group Cycling Industry Recovery, which I moderate.

I wrote, “Further to [the Group member’s comment that] ‘The combination of manufacturing bikes for their own company stores, selling bikes at these stores and selling direct to consumers online is far greater than the $$$ value of manufacturing bikes to sell to their dealer network:’ this is absolutely true, but the picture is a little—OK, a lot— more complex.

“First, D2C sales by name brands is a relatively small percentage of their sales picture overall (single digits, last time I checked). But obviously the D2C profits are a whole lot higher, since they take all of the dealers' margin for themselves (along with some other incremental savings, but let's not quibble about that here).

“This leads to a situation where, when the in-demand inventory IS available, there's a huge incentive for suppliers to sell it direct rather make it available less profitably to dealers. Suppliers will deny this to the ends of the earth, but dealers don't believe them [actually, it becomes a technical question of how suppliers pre-allocate inventory into which virtual warehouses].

“Finally, it is literally in suppliers' interests to keep the system working this way. So whether by design or (much more likely) due to their previous stupidity in over-ordering, they've turned limited availability of desirable product to their own advantage.”

Ben Coffey, national sales manager at Thomson Bike Tours, responded to my point this way (disclosure: Thomson is a former client):

“Even we suppliers who didn’t irresponsibly overproduce are sitting on inventory, because suppliers who did overproduce are slashing prices to the point where we can’t sell our product without deep discounts. It’s a mess.”

I chimed in, “Further to my oversupply point, PFB has the units as they enter the country and the overall inventory picture for suppliers by month. But those are a little deceptive because they’re showing suppliers holding fairly typical numbers of units over the past couple of years (but historically high dollars, due to FOB price increases in the post-COVID boom).

“But what those numbers don't tell us is how much of that inventory is leftovers from previous years. All we really know, anecdotally, is that it's a lot. And, further to a question others have asked, they [suppliers] can't take on new, sellable inventory because their lines of credit are all more than maxed out on the old, unsellable stuff.

“As I say, it's a really tough problem.”

Some more on this larger topic:

Jeroen Both, former chief supply chain officer and member of the board of management at Accell Group, had this to say about The Bullwhip effect. It’s a rather long quote, but, I think, worthwhile.

“In supply chain theory we know the bullwhip effect,” he said in an interview with Bike Europe dated June 10 this year, “An extreme spike in demand is always followed by a rapid decline and it then takes a while for the market to stabilize. In the past five years, a large group of manufacturers kept ordering during the spike in the market, knowing it would be followed by a sharp decline in demand. But they didn’t act accordingly.”

He continued, “Instead, we have seen procurement teams engaging in discussions driven by emotions. The GBPI [Global Bicycle Purchasing Index, jointly developed by Bike Europe, EUROBIKE and IFH Köln] would have prevented the panic buying that led to a crisis. The bicycle industry is not in transition as many insiders suggest; it is merely the next phase of the bullwhip. The industry has benefited from the coronavirus sales boom and will now experience several years during which business performance will be less favourable compared to the previous period. Never forget that the underlying growth drivers remain intact.”

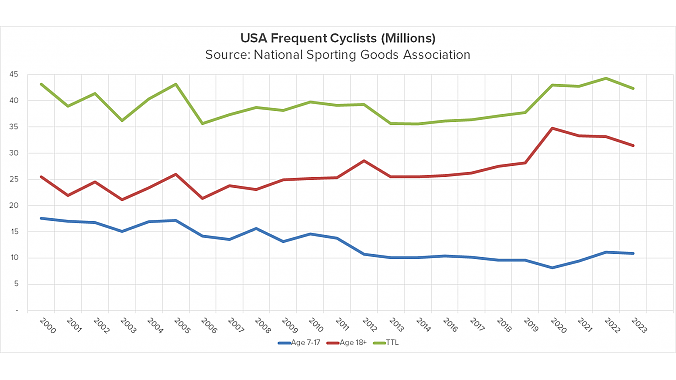

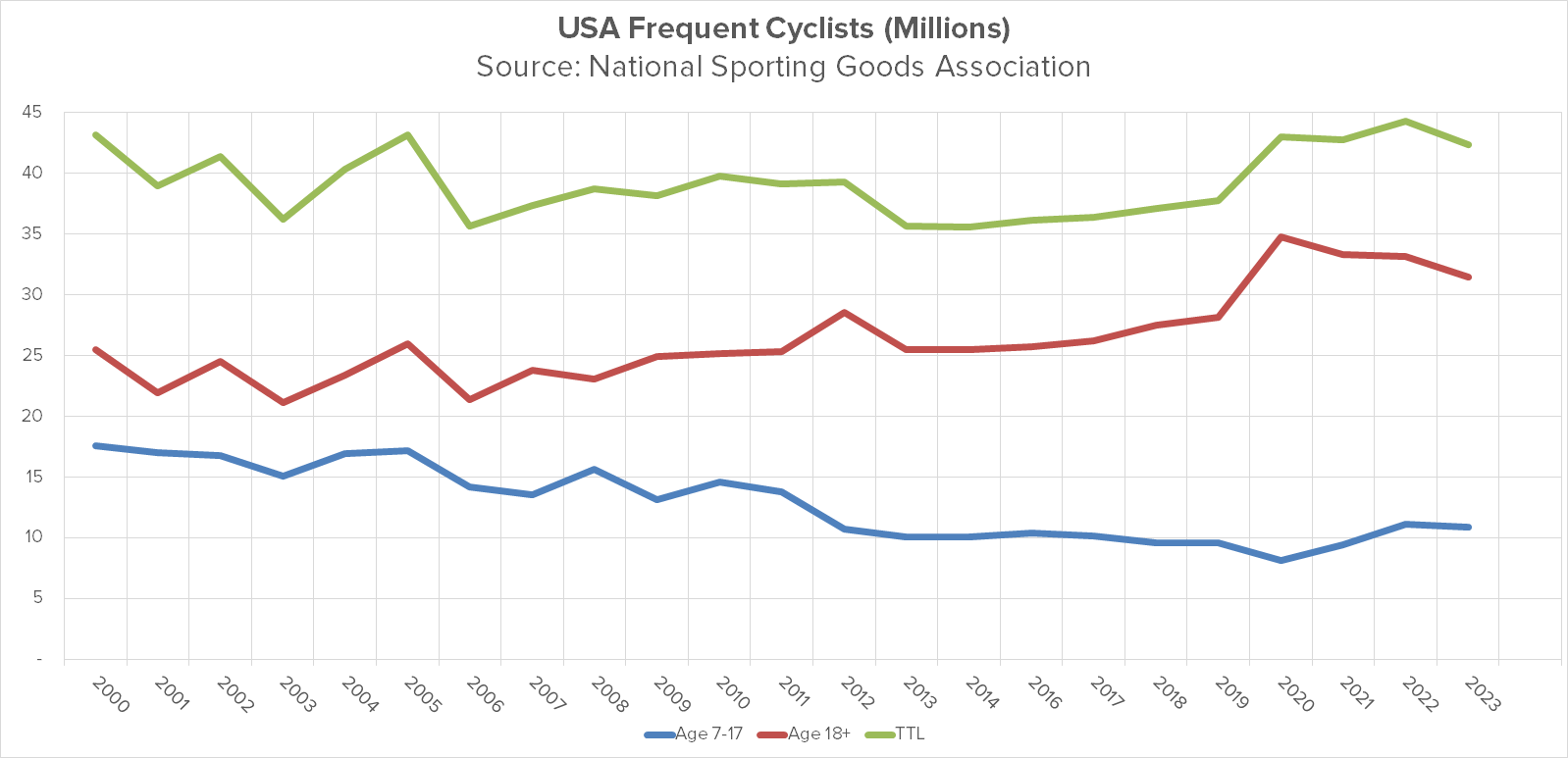

In the USA, the “underlying growth drivers” he mentions include the COVID-era ridership boost which, according to both PeopleForBikes and the National Sporting Goods Administration, continues to be strong. Here’s a graph I did as part of a piece this time last year showing the NSGA data: As you can see, it shows that frequent riders (that is, those who rode more than six times per year) continued to be stronger post-COVID than at any time since 2000. Despite this, as readers know all too well and I pointed out in the piece linked above, post-COVID sales pretty much, um, sucked. That’s a technical Marketing term.

As you can see, it shows that frequent riders (that is, those who rode more than six times per year) continued to be stronger post-COVID than at any time since 2000. Despite this, as readers know all too well and I pointed out in the piece linked above, post-COVID sales pretty much, um, sucked. That’s a technical Marketing term.

As far as what all this has to do with me mostly just copy/pasting quotes from myself and others instead of writing an actual piece this month, well, that’s a topic we’ll just have to discuss another time. Meanwhile, look forward to Part Two of this series, which is scheduled to go live August 11.

Next month’s installation will feature a fun interview with industry legend Wayne Stetina, high-level veteran of both SRAM and Shimano, plus an essay on the Game Theory problem known as Prisoner’s Dilemma, and still more categories (with examples) of industry foot off-shootery.