This month’s piece began as a long, multi-participant email chain among eight industry veterans. In no particular order, they were Blair Clark, former president of Canyon USA; Ryan Atkinson, president & co-owner at Workstand (formerly SmartEtailing); Heather Mason, president of the NBDA; Liam Donoghue, senior research manager of PeopleForBikes, BRAIN editor in chief Stephen Frothingham, BRAIN managing editor Dean Yobbi, BRAIN retail editor Ray Keener, and myself (I’m not a BRAIN editor, just a snarky freelancer).

The original intention of the discussion was to reach consensus on what seemed like a simple enough question — how many bike shops are there in the USA? The traditional number is “about 6,500,” which is from Georger Data Services survey of various bike brands’ dealer listings. This estimate has remained the same since at least 2012.

But GDS has recently been adding a lot of new e-bike retailers to its lists, some with names like Kootenai Float Company, Golf Cart Monkey, and Andy's Armory and Adventure. None of these sound like typical bike shop names, and none of them are involved with the pedal-only side of our business. But all of them sell or rent e-bikes and, more importantly, are listed as dealers by at least one major e-bike brand.

As the group began to discuss that number, it quickly became apparent that there was a larger, existential question at issue: how do we even define a bike shop in the first place?

Answer: It’s complicated.

NBDA president Heather Mason offered this definition, not of a bike shop, or even what we’ve traditionally called an Independent Bicycle Dealer, but of what she terms a Bicycle Specialty Retailer, which presumably includes NBDA members:

“A bicycle specialty retailer is a business dedicated to selling bicycles, cycling accessories, and related services, with a focus on providing expert knowledge and exceptional customer service. These retailers come in diverse shapes and sizes (single store, multi store, mobile and other) but all share similar characteristics as they cater to a diverse range of cycling enthusiasts, from casual riders to competitive cyclists, and typically offer personalized services such as bike fitting, maintenance, and repair.”

She goes on to say that key characteristics of bicycle specialty retailers often include expertise, a curated selection of bicycles and equipment/accessories, community engagement, customer service, and advocacy for cycling.

That’s a pretty good definition (I note it seems to omit bicycle rental businesses, although that may be covered under “related services”). But it’s not very actionable for purposes of determining how many bike shops (or even bicycle specialty retailers) there are. For instance, who defines “expert knowledge and exceptional customer service,” and how do you implement that definition in a count of bike shops?

My own definition is a lot broader: A bike dealer is “any retail business that sells, rents, or services bicycles and/or related equipment.” E-bikes count as bicycles, and fitting comes under “services.” Although it does have the advantage of being short, it’s even less useful than Mason’s definition above for purposes of counting bike shops. And it puts sporting goods, online retailers, and mass market retailers in the same bucket as traditional brick-and-mortar bike shops, which hardly seems right.

So what’s the best solution?

Two lists, one basic concept

For years, the NBDA count — later sold as The Bike Shop List — was the only and best estimate of the retailer dealer market available to the industry.

In the early days, the NBDA counted IBDs with a troika of definitions. To qualify for a listing as an IBD, a business had to have a physical storefront address, be open all 12 months of the year, and have more than 50% of its business devoted to bikes and cycling equipment. A source list of some 4,000 dealers provided by the NBDA was vetted by live person-to-person phone calls to every shop owner on the list (yikes!), according to Jay Townley, who conducted the surveys on behalf of the NBDA.

This methodology led to a dealer count of not quite 6,300 locations in 2001 which steadily declined to just over 4,200 in 2010, a loss of one-third as the retailer market evolved in the new millennium.

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, a couple of contemporary sources estimate that an average of 2-300 bike shops go out of business per year in the 2010-2019 era, which would make the NBDA numbers, if correct, almost double that. The same sources tell me we normally add the same number of new dealers each year, giving the dealer population an average net loss of essentially zero.

For years, the NBDA count — later sold as The Bike Shop List — was the only and best estimate of the retailer dealer market available to the industry. But did the industry really lose more than 2,000 dealers in the first decade of the 21st Century? It’s hard to say, but it seems to this observer that an average loss of 500-plus dealers each would have been a lot more noticeable than we were aware of at the time.

The NBDA definitions encompassed most traditional brick-and-mortar bike shops, and effectively excluded exclusively mail-order (and later, internet) businesses, sporting goods stores, and mass market retailers. But the results excluded seasonal businesses and non-responding dealers. And, most important, they also excluded any dealers that were not on the original NBDA source list.

Then, starting in 2002, Christopher Georger and his company GDS instituted a new way of defining and counting bike shops. As mentioned in the previous section, a business was deemed a bike shop if it was listed as a dealer in one or more selected brands’ internet dealer locators. This is the methodology that led to the “about 6,500” dealers number that has stayed with us so long.

Georger’s revolutionary methodology was to “scrape” (an internet term) many of the industry’s dealer locators, and then cross-check and compile the results.

Nowadays the GDS list has grown to include shops listed as dealers by some 84 “popular brands” (including e-bike brands), mostly as requested by GDS clients. The list does not include stores without physical addresses, which excludes some mobile bike shops and internet-only stores. Sporting goods stores like REI, Scheels, and Dick’s are included since they are listed as dealers by one or more of the reference brands.

The current GDS list includes some 8,500 dealer locations (“doors,” in marketing parlance), not including about 400 clothing stores that sell cycling-related brands, or some 200 mobile shops without ascertainable locations.

In terms of what Georger calls “pure” bike shops — those selling one or more of his listed pedal-only brands, and which may or may not carry e-bikes — that number has grown to about 7,000 as of this writing. This includes almost 4,000 shops that carry one or more of the Top 4 bike brands: Trek (not including Electra, which is counted separately), Specialized, Giant, and Cannondale (not including other brands owned by Pon). That leaves approximately 3,000 listed bike shops that do not carry any of the Top Four brands, more than 40% of the total dealer population.

E-bike-only stores add another 1,500 locations, to reach a total of about 8,500 bike shops of all types currently doing business in the United States.

Perhaps ironically, the GDS dealer count is also called The Bike Shop List. (Georger says the name was obvious and he was unaware of Townley’s earlier version when he acquired the URL.)

Most recently, Peter Woolery, for more than a decade CFO of the Summit Bicycles chain of stores in the Northern California Bay Area, has been tracking brands and retailers through his company, Bicycle Market Research, in addition to the other research his company does.

Woolery uses bots to scrape the dealer lists of some 90 bike brands. These are drawn from his proprietary list of more than 950 (!) bike brands sold in the country.

“It’s a very long tail of small brands,” he said, “many of which are D2C.”

About half of these 90 selected brands offer e-bikes as well. Woolery also gets and vets dealers through third-party companies like locally.com, which offers store locator services and provides the dealer list engines for many bike brands.

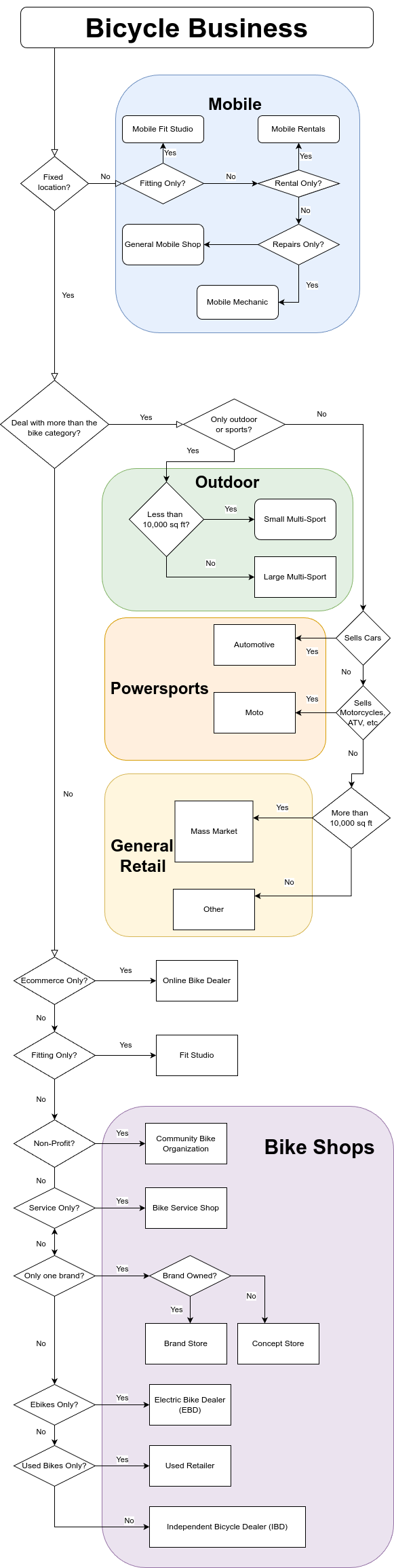

He then sorts dealer types into a series of six categories and 19 “buckets” (in no particular order) according to the flow chart on the left.

(Click here for a resizable version)

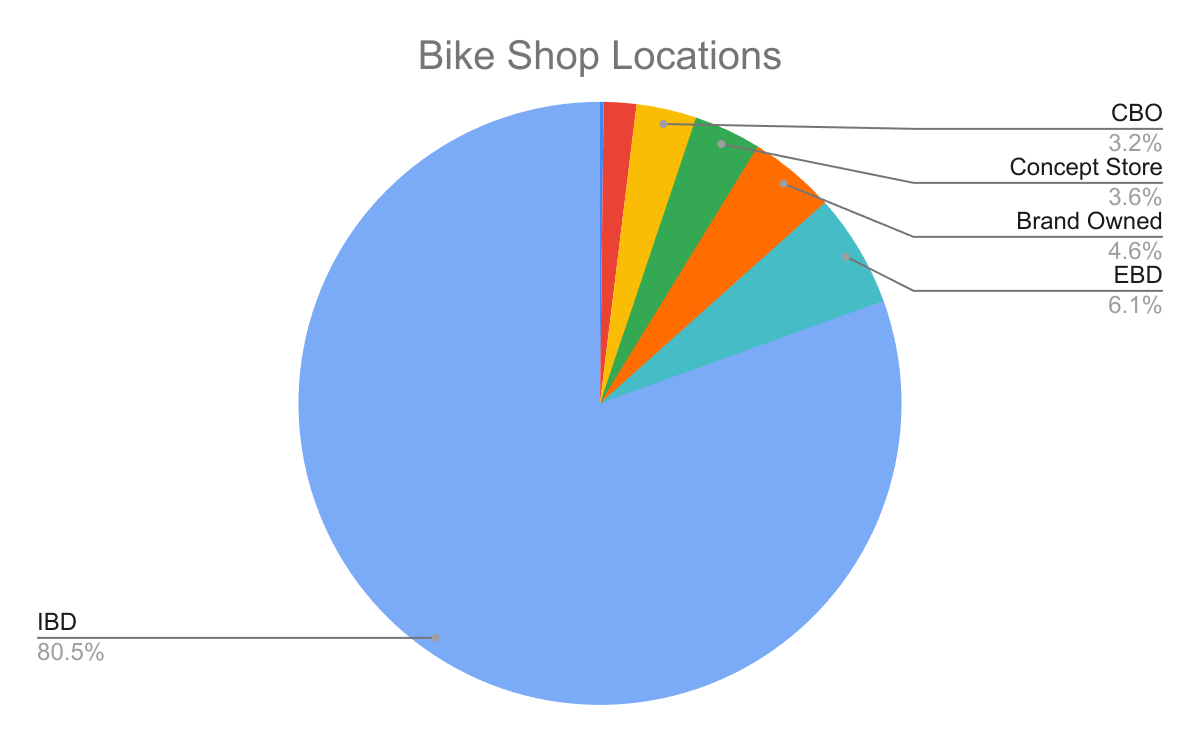

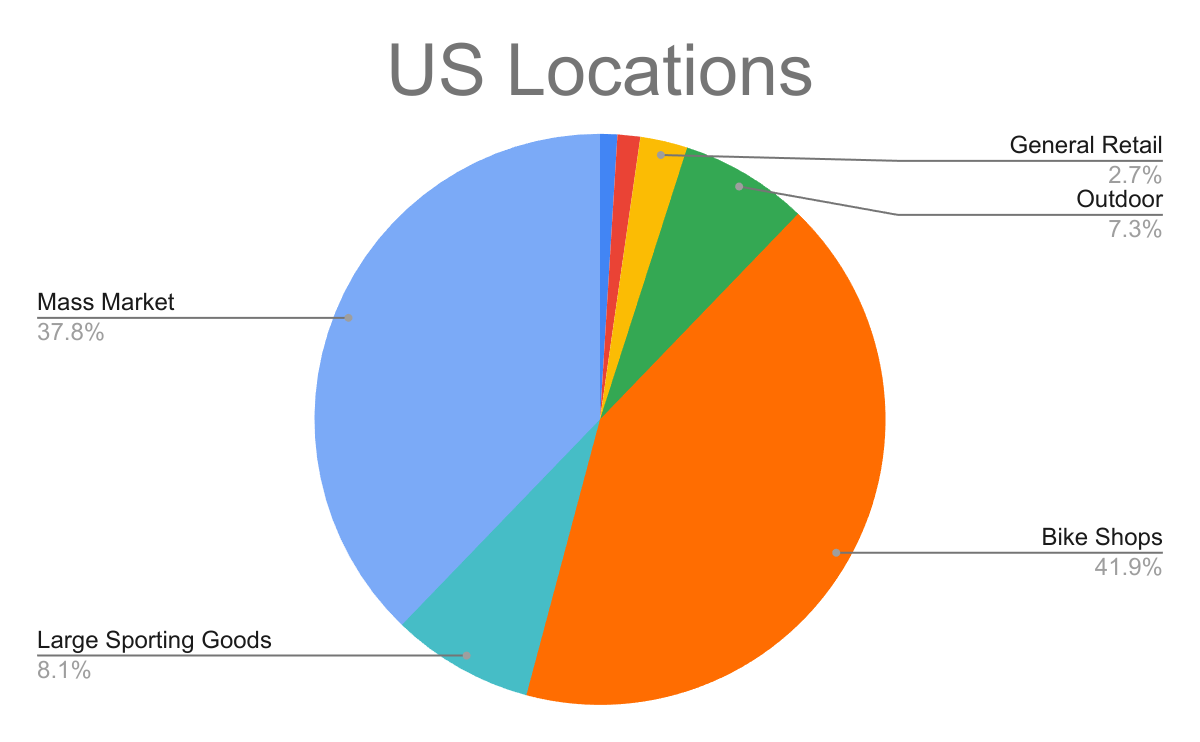

To review, the categories and buckets are as follows. Mobile: fit studio, rentals only, general mobile shop, and mobile mechanic. Outdoor: large and small multisport stores. Powersports: automotive, and motorcycle. General Retail: mass market and other. Unnamed category: online-only bike dealer, and fit studio. Bike Shops: community (nonprofit), service-only, brand-owned stores, concept stores, e-bike-only dealer (EBD), used-bike-only retailer, and independent bicycle dealer (IBD).

That’s a lot of buckets. The beauty of this method is you can define whatever group of retailers you prefer and (for a price) get a count and a comprehensive list of dealers from the buckets you’ve selected.

The results are impressive, and so is the methodology. Woolery gets his used or community shops by working with Ray Keener’s list and with Yelp data, which can be filtered for bike services. The community dealers are then cross-referenced with the IRS’ list of nonprofits.

How does he get (and separate) brand-owned and concept stores? “That’s definitely trickier,” he says, “depending on the brand.” Trek’s owned stores all link back to Trek. Specialized is a lot fuzzier, including its InCycle marque and its other stores. Pon has far fewer dealers, so they are easy to identify by following Mike's Bikes, Woolery said.

Scheels, REI and Dick’s, among others, are classified as large multisport stores (Circana included them in their "Rest of Market" channel). And although they don’t get their own bucket, BMX brands’ dealer locaters are also scraped. “When you’re focused on BMX, you have to have some mainline brands like Haro or GT, and that gets us in the door,” he says.

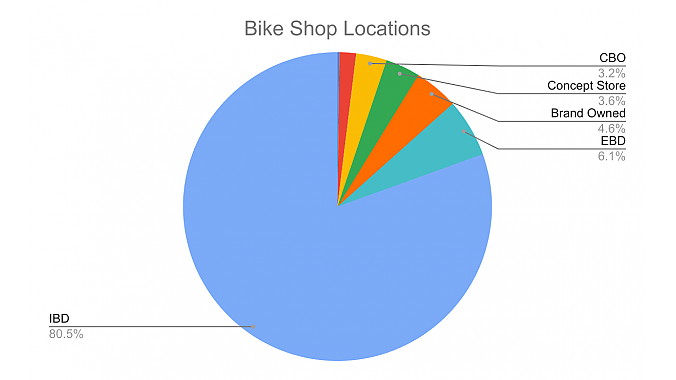

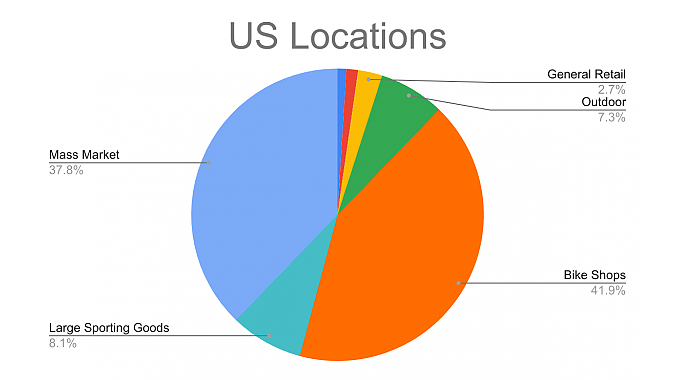

On the right are a couple of charts showing how the various categories stack up relative to each other and how the individual buckets within the bike shop category rank. All charts in this piece are property of Woolery’s Bicycle Market Research company and are used with permission. Note that CBO is Community Bike Organization.

The strength of both Georger’s and Woolery’s results are that they are so comprehensive. Their weakness is that they’re only as good as the dealer locators they’re drawn from and the vetting the research company does.

Critics have told me that brands’ dealer lists are artificially inflated with shops that have either dropped the line or gone out of business entirely. While there are a number of brands (mostly e-bike) that list every shop that’s ever sold or even repaired one of their products as dealers, I personally do not find this argument persuasive. Brands in general have no incentive to send prospective customers to nonexistent dealers. This gives them a strong reason for keeping their dealer locators current and accurate. And cross-checking and vetting their information by the research companies helps ensure the quality of the end data.

To go all the way back to the top of this piece, more than 2,000 words ago (and thanks for reading this far), how many “real” (non-EBD) bike shops are there in the USA?

GDS says about 7,000. BMR says about 7,500. What I find remarkable is how close these estimates are to agreement — a relatively slim 7% difference. EBDs add another 1,500 to this equation. That’s a lot more than the traditional “about 6,500” figure.

As to the Big Question of what makes a bike shop a bike shop, well, the current best answer seems to be that it’s pretty much whatever bike suppliers say it is. I know that’s not a definitive answer by any means, but it’ll have to do until the real thing comes along.