Back in October of 2019, I wrote about the Bike 3.0 model's failure to achieve its ultimate goal of top brands' market dominance and effective control of the overall bicycle marketplace. That's still true more than a year later.

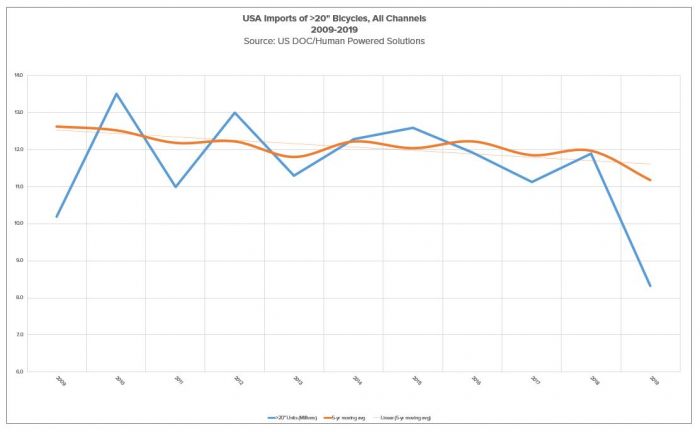

The market itself has been changing since we emerged from the Great Recession of 2008, which hit industry imports in 2009 and left us with a decade-long flat market. This continued until the huge import decline of 2019, which significantly contributed to the product shortages of the COVID-driven market in 2020 (and likely 2021, if not longer).

Within that flat market, the only way for brands to grow market share is by taking it away from competitors, either by adding dealers to their distribution network or increasing sales among the dealers they already have.

After nearly two decades of the evolving 3.0 model, here are five observations on what that evolution looks like.

1. The Tier One dealer base remains stable

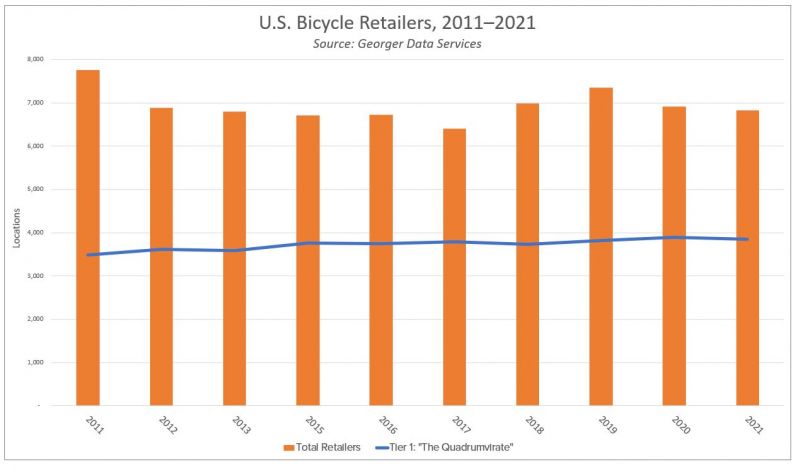

As a percentage of total retail locations, the top four brands in Tier One — Trek, Specialized, Giant and Cannondale, also known as The Quadrumvirate — have remained essentially flat for the past ten years, averaging about 53% of the dealer population. The identity of those retailers may shift as brands add or remove or acquire shops outright, but in terms of brand penetration via storefronts, the picture hasn't changed significantly in a decade.

2. Increasing margin pressure on small shops

Both anecdotally and by reviewing Tier One brands' dealer plans for the past several years, we see that while large retailers' margins have remained consistent, overall margins for the smallest retailers — especially those who don't agree to floorspace requirements — have eroded significantly.

Consequently, smaller stores are opting to floor more and more of a single brand's inventory to qualify for better margins. From this, we can conclude that total unit sales for those brands have increased among smaller dealers. In other words, the brands have been relatively successful at growing market share within the smaller shops in their dealer base.

3. Larger dealers are supporting more top tier brands

Conversely, there is some evidence that larger (and in terms of program margins, more profitable) shops are increasingly adopting a strategy of carrying more than one of the top tier brands — as more than half (55%) of Tier One retailers did in 2020.

The Quadrumvirate has gained more control of smaller shops, but paradoxically now enjoys less control with the larger ones.

Key dealers are simply playing off one Quadrumvirate brand against one or more of its competitors to prevent any one brand from becoming ascendant. This may solidify the market share of Tier One brands as a group, but only increases gridlock among the individual brands.

If the 3.0 endgame was for a single bike brand to eventually dominate the market by gaining control of the largest and/or most powerful shops, precisely the opposite has occurred: Individual Quadrumvirate brands have gained more control of smaller shops, but paradoxically now enjoy less control of the larger ones.

A notable exception is Trek's campaign to acquire ownership of successful shops in key market areas.

4. The COVID bike boom changes everything

For the past six months (and possibly the next six or more), the biggest problem faced by bike brands of all sizes is simply getting enough product to fill demand. It's hard to expand your market share when you can't effectively service the share you already have. At the same time, as I wrote in November, the balance of power between retailers and suppliers is shifting.

Suppliers are demanding — and in most cases, getting — long-term commitment from retailers for an entire season's worth of bikes in advance, a tactic that shifts inventory risk to retailers. At the same time, many retailers are adding brands to their portfolio as a way of spreading their exposure if any one brand is unable to honor its inventory commitments, as consistently happened in 2020. This is true across all brands in the market, not just Tier One.

There is no evident winner in this struggle; what is significant is that it's happening at all. The open question is what will occur in the dealer/supplier dynamic as the mini-boom wanes, whether that comes about sooner or later. And no one can say with certainly when that's going to happen.

5. The IBD business model itself is evolving

Bicycles have traditionally been a low-margin proposition, according to the NBDA's Cost Of Doing Business studies going back nearly 30 years.

The rise of internet sales has upended the retail paradigm. Competition from online discount companies has driven dealer margins in the once-profitable equipment category to all-time lows.

The conventional retail strategy was to accept low margins on bikes as a way to get riders into the store, then earn higher margins on equipment sales to those riders over time.

The rise of internet sales has upended this paradigm. Not only are more consumers buying equipment online instead of from their local shop, but competition from online discount companies has driven dealer margins in the once-profitable equipment category to all-time lows.

Retailers have responded by increasing their service offerings, adopting new categories like used bikes, rentals, and coffee and/or beer sales. Some shops are even looking to reduce inventories or decrease shop size entirely to compensate for the critical loss of equipment revenue.

Given this evolving business model and the direction it's taking, it's difficult to see top brands increasing their market share anytime soon ... which means it's likely the Bike 3.0 model will continue limping along in its current mode for years to come.

Rick Vosper has been helping companies in the bicycle business solve marketing problems since 1989. Email rick@rvms.com for a free consultation.