In Part One of this series, we looked at the fact that while more retailers are offering assembly services, the market for D2C bikes seems to be a lot smaller than conventional wisdom would suppose. The plain fact is that brick and mortar operations will continue to command the lion’s share of the new bike business, especially at specialty retail price points. Part Two explored the implications of SKU proliferation and inventory requirements on retailers’ bottom line with industry profitability consultant and fellow BRAIN columnist David De Keyser.

In this third and final installation, I return to dealer fulfillment of D2C bikes and what it may mean in the longer term for retailers, consumers, and the entire specialty retail channel.

Integrating D2C bikes into the brick and mortar marketplace

Let’s begin with three working assumptions:

First, direct-to-consumer is at best a modest segment of IBD-quality bike sales. We covered this back in Part One, and there is a growing body of both confidential and public-source data to confirm it.

Some significant and growing portion of that high-end D2C segment demands professional-quality (which is to say, IBD-quality) prep and assembly. This is true both from the consumer end and — even more critically — from the supplier end of the equation.

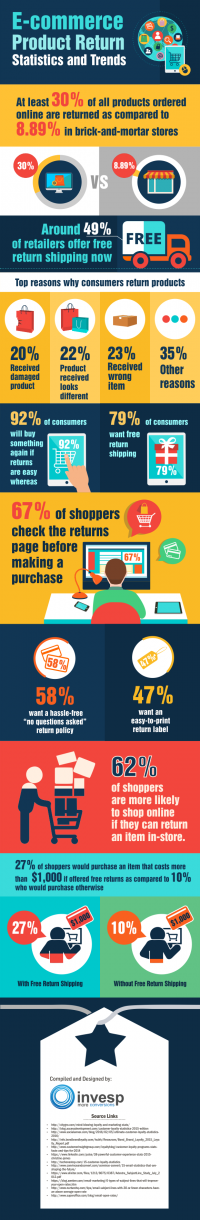

Second, the cost of returns is already a multi-billion dollar headache for internet retailers. According to this Financial Times article, “U.S. consumers are expected to send back a record $100 billion worth of unwanted goods bought between Thanksgiving and Christmas [2019] as the rise of e-commerce causes a returns epidemic. Online purchases are almost three times more likely to be returned than those in stores, leaving retailers with millions of items to sort.”

To be sure, the huge majority of those returns is on items like clothing, where customers are ordering multiple sizes and high return rates have no immediate impact on customer satisfaction. But what happens to a high-end bike brand when slipshod assembly by low-bid contractors starts eroding the brand’s reputation? Even worse, what happens when that sub-par assembly is on assembly-intensive models like aero road or tri bikes, or full suspension off-road machines or high-end e-bikes?

Retailer Peter Woolery is chief financial officer for the five-store Summit Bicycles chain in Northern California. He makes it his business to track this sort of thing. “We definitely see an elevated return rate from online sales,” he says, “though the numbers I see for retail broadly are way higher than our experience. It’s 10%-30% for retail overall; 1–3% for our brick and mortars, and 13% for online.”

So four and a half to 13 times the return rate for online sales in the bike business. More important, the cost of return freight on bikes is an order of magnitude higher than for a pair of socks, and the potential effect of poor assembly on a brand’s reputation is well-nigh incalculable.

Offshore manufacturers of low-end products half a world away have no-return policies for exactly this reason. At the end of the day, they have no intention of absorbing additional freight costs, and they don’t care about reputation, because they’re not traditional brands—just containers full of commodities with logos attached. But no supplier of IBD-quality products can afford that kind of damage to its brand image. Which brings us to my third and final working assumption:

IBD-quality bikes ultimately demand IBD-quality assembly and service. Which is to say, assembly and service from professional bicycle retailers, whether brick & mortar or mobile. In the long run, the market will demand it from both from the consumer and supplier ends. And brands that fail to honor market demands are brands that soon end up out of business.

This puts huge and hitherto unsuspected power directly into the hands of bike shops, both with respect to D2C bikes and, as we shall see, with their traditional suppliers. More about that in a bit.

Creating a D2C assembly & service marketplace

Currently there are four ways a bicycle retailer can become a D2C assembly/builder and services provider. First, a consumer can come into the shop with the product in tow and negotiate a price and terms. Alternatively, a shop can contact the manufacturer and offer to become a services provider for its products.

Third, and increasingly common, the retailer can become a member of a group like VeloFix or Beeline, which lists them as an assembly partner with supplier brands.

VeloFix, for instance, is the assembly/delivery partner for Canyon USA, Rad Power, and other D2C brands. It’s a franchise operation, and you buy in to become a franchisee. After initially playing in the franchise space, Beeline now uses a membership model based on its software platform and charges retailers a monthly fee, according to the company’s website. According to the same website, Beeline has contracts with Raleigh, Diamondback, Cleary and other brands.

But there is also a fourth option, and one which I find particularly intriguing.

Velotooler is a, well, I dunno, exactly. Marketplace? Value-added services aggregator? Even Velotooler CEO Terence Finn doesn’t have a precise word for it, although he prefers Facilitator. But here’s how it works:

D2C assembly and service is rapidly becoming a fact of life for the cycling industry. It’s also a potentially lucrative revenue stream for retailers, not to mention an effective solution to the Last Mile problem for all parties involved

Retailers/service providers list themselves for free on the Velotooler website with whatever services (including delivery) they want to offer at whatever rates they think appropriate. Consumers select a service provider based on location, price and —this is vital — consumer feedback ratings. In theory, this means providers who do higher-quality work on higher-quality bikes can receive higher-quality compensation. At the end of the day, the market decides. Velotooler takes a sliding percentage of each transaction, depending on client volume and overall price. Suppliers can also set rates for various product classes, which retailers can choose to accept or not.

The thing I like so much about the marketplace concept is that it’s completely agnostic with respect to retailers, brands, and consumers.

The point of all this, regardless of fulfillment model, is that D2C assembly and service is becoming a fact of life for the cycling industry. It’s also a potentially lucrative (if modest) revenue stream for retailers, not to mention an effective solution to the Last Mile problem for all parties involved.

Industry impact on an impacted industry

But the most significant thing about The Last Mile solution is not that it’s going to be a game changer by itself, at least not in terms of share of the specialty retail channel. That will happen (or not) based on market forces. The big potential disruption comes as the emerging D2C marketplace shows us a way to change the very nature of how retailers interact with bike brands, and eventually how the industry and the larger market values the role of brick and mortar bike shops to begin with.

Ignoring the value-add question has allowed mainline brands to pretend that it is effectively nonexistent. Instead of raising prices to reflect the increased value retailers bring, brands are struggling to reduce pricing to bring their products closer to parity with online competitors.

If retailers can make better net-net margins from assembling bikes they don’t have to inventory, what does that mean for how traditional brands bring their products to market?

Currently, we have the Quadrumvirate model, where (in most cases), shops trade away floor space and high inventory loads for better margins, a practice I call Invendentured Servitude. Basically, the supplier tail wags the retail dog, controlling the marketplace to an (in my opinion) unprecedented degree and effectively turning some near-majority of US retail locations into factory outlets for a few dominant brands. At the same time, the NBDA’s Cost Of Doing Business studies show us the high costs associated with all that inventory means most-typical retailers (what statisticians call the median value) barely break even on their main brands at the end of the year. And this has been true literally for decades.

Worse, the remaining sixty-odd mainline bike brands fall right in line, working on some less onerous variant of the Quadrumvirate model instead of making their brands more appealing to retailers through higher margins, lower inventory costs, or more creative ways of putting those products on dealers’ floors. (These could take the form of flooring plans, consignment inventory, low-cost demo models supported by next-day delivery of fulfillment stock, or literally a dozen or more alternatives.) Yet this simply isn’t happening, largely because there’s no market force demanding that it happen. At least not until now, with the advent of the D2C marketplace.

If the D2C movement teaches us anything about the specialty retailer channel, it’s that there are other ways to skin that supply chain cat, ways that can work out better for both suppliers and retailers in the long run.

Underlying all this is an enormously important question the industry has been content to ignore for entirely too long: exactly how much value does a brick & mortar retailer add to a bicycle sale?

Ignoring this question — and retailers’ almost stupefying tolerance of its implications — has allowed mainline brands to pretend that retailer value-add is effectively nonexistent. Instead of raising prices to reflect the increased value retailers bring, brands are struggling to reduce pricing to bring their products closer to parity with online competitors. This fear-borne policy is reactive, unwise, and ultimately absurd.

As I said back in Part Two of this series, it’s a huge Catch-22: the retailer is expected to add more value to the traditional bike sale, but is actually compensated less for it overall. The inescapable conclusion is that dealers are literally being punished for increasing the value they deliver for traditional bike brands.

Also in Part Two, we heard from retail profitability consultant David De Keyser, who had some sharp words for the future of the traditional brand model, especially as expressed by the industry’s leading players. "Something's got to give,” he said. “There definitely needs to be more balance. At a certain point, you can't keep rolling back the margins and increasing the inventory demands before something pops.”

De Keyser was even more emphatic in a follow-up discussion we had about the opportunity for alternative retail sell-in models. “The solution,” he says, “has to be for mainline suppliers to increase dealer margins. That either comes from their own pockets or in the form of higher retail prices. The big guys didn't get big just by being bullies, they also have to be pretty smart. And at some place they have to make an appeal to the retailers' bottom line, or they're going to lose business to smaller brands that do."

And in solving the Last Mile Problem, the emergence of the D2C marketplace has provided some tantalizing clues as to how those smaller brands might accomplish exactly that.

Will that become the start of a new era, a Bike 4.0? Hard to say. Despite all its shortcomings and challenges, the 3.0 model has been with us since the early 2000s. But there have been thunderclouds gathering on the 3.0 horizon for years, as retailers grow increasing unhappy with their piece of the pie. And if some innovators can offer them a larger slice of that pie, there is every opportunity to disrupt the entire 3.0 paradigm.