It is axiomatic that in a flat market, the only way for a brand to grow is by taking market share away from its competitors. Unlike the product-driven Bike 2.0 era, the bike industry is currently a zero-sum game, where in order for anyone to win, someone else has to lose ... and preferably as many someones as possible.

As discussed previously in this space, the Bike 3.0 era (roughly 2000 through present) is focused on a few of the largest bike brands (the Quadrumvirate) attempting to gain dominance by aligning themselves closely with a relatively few leading retailers in each market. The key behind this strategy is to cause competing brands and retailers to fail, growing market share for the survivors. The model comes in response to the forces of perfect competition that characterized the 2.0 era (roughly early 1980s through 2000). But best evidence to date indicates the 3.0 strategy hasn’t worked.

More specifically, the 3.0 model has stalled for three critical reasons: failure of the limited exclusivity model in the face of perfect competition, underestimation of the impact of online bicycle sales, and the subsequent late entry of the largest players’ omnichannel strategy response.

1. Failure of limited exclusivity

The 3.0 model is predicated on a few brands growing market share through attrition and consolidation, both among competing brands and the retailers they supply. But the numbers show that has not happened.

It turns out the perfectly competitive market’s low barrier to entry is creating new retailers (who then provide a channel outlet for competing suppliers) just as fast as competition causes the weaker players to fail. This is happening despite ever-increasing pressures on retail margins across all product categories, and it can be confirmed by looking at the overall number of retailers in the channel, which has remained fairly constant since at least 2012, according to two independent sources:

- Georger Data Services, which shows approximately 7,000 location listed as retailers for about 60 bike brands that the company tracks.

- QBP dealer lists, which have remained steady at about 7,000 locations representing about 5,400 business entities, according to QBP president Rich Tauer.

To be sure, bike shops are failing (or at least dropping off the QBP list) at a rate of about 400 locations per year, according to Tauer. But — and this is key — they’re being replaced at about the same rate. Simple arithmetic (400 retailers per year in a base of 7,000) yields a retailer churn rate of 5.7%, which is relatively modest as such things go.

The net retention of retailers is significant, both because it contradicts the Bike 3.0 premise of pending market collapse, and because it does so at a time when retailers in other industries (think Sears, Borders Books or Toys “R” Us) are undergoing what’s being termed the Retail Apocalypse. In a sense, the forces of Perfect Competition may have inoculated the bike business from the kind of collapse that has plagued so many other consumer product categories.

In a classic instance of industry denial, we in the specialty retail segment effectively blinded ourselves to the approaching freight train that was online bicycle sales.

A typical alternative distribution strategy (as implemented by Nike and many other brands) would be for the Quadrumvirate to simply open more and more retailers, pushing other brands out of the channel until it reaches market saturation, the point at which adding more distribution points no longer increases sales. But the very nature of the 3.0 model is to have fewer retailers with a relatively greater commitment to a specific brand.

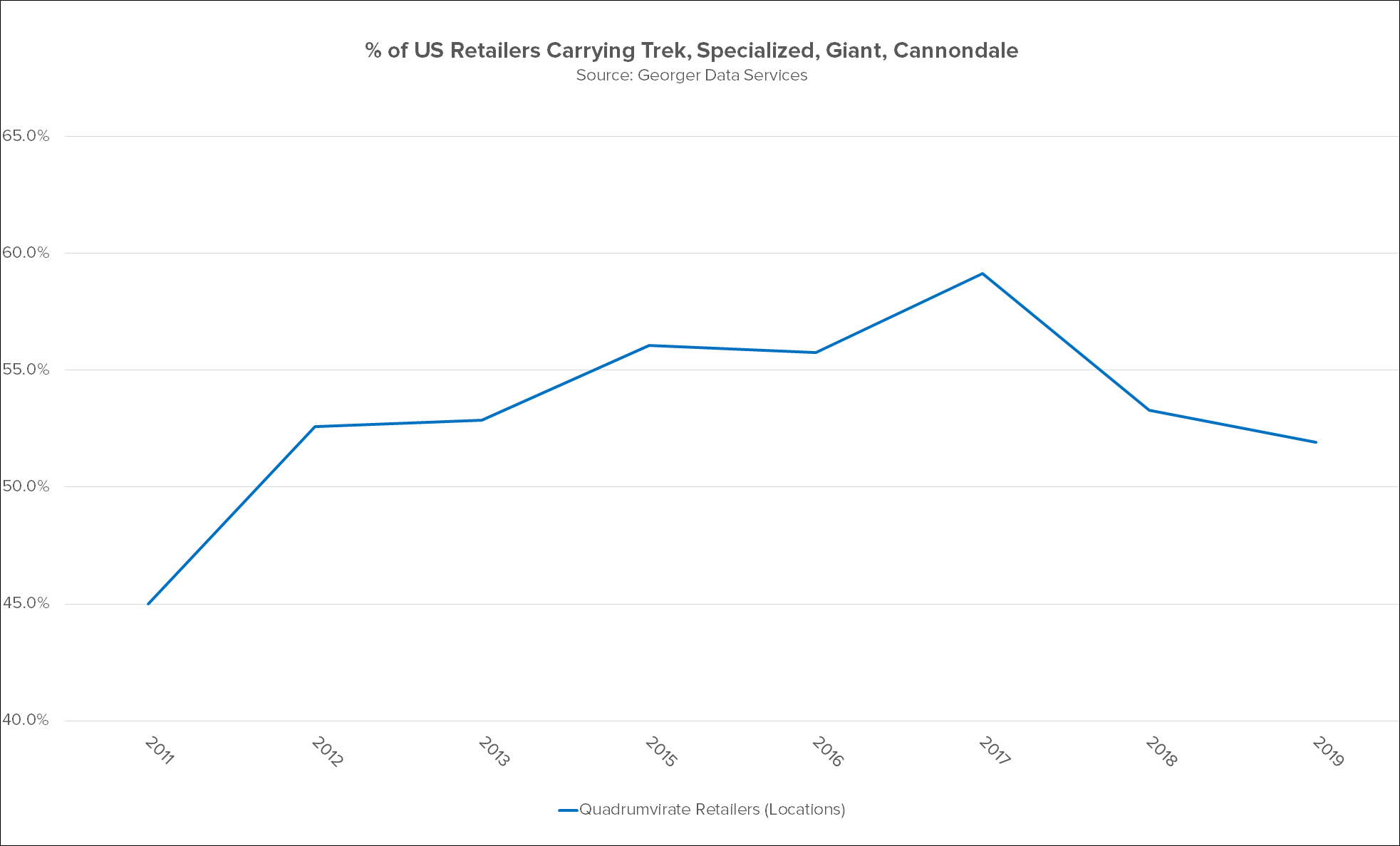

Opening some large number of additional shops would violate the basic 3.0 covenant and, despite retailers’ fears, has simply not proven to be the case. In fact, the GDS data shows that after a steady period of increase from 2011 to 2017, there are now relatively fewer retailers carrying the top four bike brands (51.9%) than at any time since 2012 (52.6%).

2. Underestimating the Internet

The earliest statement of the 3.0 principle came in the form of a letter from John Burke to Trek retailers in late 1997, promising to do more business with existing Trek dealers by, among other things, working more closely with them for their mutual success.

Specialized responded with a similar initiative, the Specialized Dealer Alliance, in 1999. The success of those plans quickly forced competing bike brands to either follow suit with their own 3.0 programs or risk losing floor space at key retailers nationwide. And the strategy worked, as an elite four brands — Trek, Specialized, Giant and Cannondale — gained and stabilized a collectively dominant market share.

What none of those companies (or virtually anyone else in the industry) foresaw was the rise of consumer-direct bicycle sales via the internet.

To be fair, the Bike 3.0 model was developed in the middle of the dot-com bubble — and its subsequent bust — at the turn of the millennium, which found more than half of all dot-com startups went out of business by 2004. The prevailing wisdom in those years was that a consumer-direct channel for bicycles could never be a significant part of the market, both because early efforts by Performance and others had proved disastrous, and more importantly, because any name brand crazy enough to try it would find itself locked out of traditional bike shops forever.

Another factor was the industry’s self-inflicted blindness with respect to online brands. Because it only collected sales data from its own customers at the time (which is to say, brick-and-mortar bike shops), suppliers had no way to see the steady rise in bike sales from online marketers like REI, competitivecyclist.com or others, including a resurgent Performance.

In a classic instance of industry denial, we in the specialty retail segment effectively blinded ourselves to the approaching freight train that was online bicycle sales. As for a certain German upstart that began in 2001, Canyon Bicycles GmbH was a purely European problem, and one the U.S.-based players wouldn’t begin to take seriously until much later.

3. Omnichannel: 10 years too late, $100 million too short

Massive ignorance of the size of the internet-fueled consumer direct channel — doubtlessly abetted by fears of dealer retaliation — delayed the introduction of click & collect programs by the largest bike brands by more than a decade.

It is entirely possible that some large majority of Quadrumvirate C&C revenues are coming from sales that would have occurred in any case … which would mean that, instead of increasing sales overall, those brands are merely transferring profit dollars out of retailers’ pockets and into their own.

The first of these was Trek Connect, premiered in August of 2015. Others followed, until all four of the largest players had C&C programs and an overwhelming majority of other bike brands were sold online, if not via click and collect, then consumer-direct outright.

Never mind that all these sales were in violation of the NBDA’s 2013 position paper Commoditization and eCommerce. That document has since been removed from the NBDA website. (But the internet is forever. Here’s a link to a saved copy.)

To me, the NBDA’s position shift on click & collect is not so much an abdication of principles as the recognition of a fundamental reality. The rise of internet-based bicycle sales has created its own industry sales channel, one with the power to move markets. And, as with any other reality, we ignore this one at our peril.

According to a slide from Trek’s dealer presentation earlier this month, Canyon’s current U.S. sales are $28 million. Think about Canyon’s market share in relation to other online vendors. Now factor in Amazon resellers, bikes that make their way out of traditional retailers’ back doors via eBay or other means, and the huge sales volume of offshore retailers like Wiggle, and it’s easy to see how the annual consumer market for online bicycles might top the $100 million mark.

Now compare and contrast that with the combined click & collect output of the Quadrumvirate. It seems obvious that consumer-direct/dealer-fulfilled sales by those four brands is a small fraction of the consumer-direct total. Not only that, it’s an open question whether large brands’ C&C efforts create any significant net gain in bike sales at all.

It is entirely possible that some large majority of Quadrumvirate C&C revenues are coming from sales that would have occurred in any case … which would mean that, instead of increasing sales overall, those brands are merely transferring profit dollars out of retailers’ pockets and into their own. The dirty little secret of click and collect is that its true value to brands lies in gaining control of the sales process early on, preventing retailers from switching the sale to a competing brand once the customer is on the shop floor.

At the same time, one stated intention of Bike 3.0 programs in the early 2000s was to raise retail prices and dealer margins. The goal was both to create differentiation for those brands, as well as making them more desirable to leading retailers in each market. But price pressure from online competitors (among other factors) has produced precisely the opposite effect, and there is some evidence the brunt of that pressure has fallen disproportionately on traditional bike shops in the form of ever-lower margins.

The zero-sum reality

So, if the 3.0 model as originally conceived has not allowed top brands to achieve their goal of outright (as opposed to collective) market dominance, what will? Increasingly, the attempted response has been to put pressure on competing brands and retailers by poisoning the industry well whenever possible. I’ll unpack three major examples of this practice in Part Two of this series.