Zoom out far enough and anything can look simple. Here in the bike business, our supply chain is pretty basic.

It's a product-focused model. Suppliers design products they think people might want to ride or own, sometimes with market research, but usually the kind of products they'd want to ride or own themselves. Factories produce, aggregate and finish those products. They're shipped to the supplier, who distributes them via a network of independent retailers. Retailers sell those products to consumers who hopefully enjoy them and come back for more.

So, factories and suppliers make and distribute products, retailers sell them and customers buy them. Sounds simple, right? And it is, until you look at the fact that the model is not as successful as it might be.

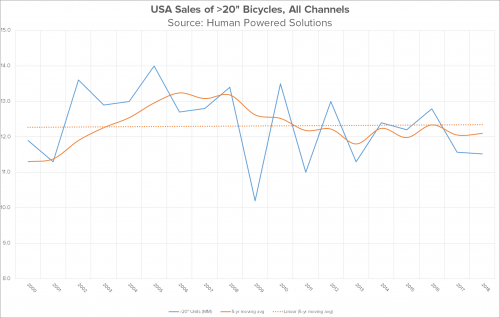

Here's proof: Bike units have been essentially flat since the turn of the millennium.

The chart below (click to enlarge) comes from Jay Townley's Human Powered Solutions company. In it, the spiky blue lines are the annual numbers we usually see. The smooth orange line is a rolling five-year average. And that flat-as-a-skillet dotted orange line? That's the linear trend over 18 years. It's actually up about 10% since 2000, but as you can see, the rolling average has been below trend every year since 2010.

The illusion of growth is what we keep hearing about the four largest bike brands, what I like to call The Quadrumvirate, which is in fact growing. What's a whole lot harder to see is all the dozens of smaller brands shrinking at more or less the same rate.

We keep telling ourselves, "Yeah, units are down but that's OK, because prices and therefore dollars are up." But that's a convenient lie, because it doesn't factor in the changing cost of money. Today's U.S. dollar is worth about half — 54 cents, as of this writing — compared to what it was in 2000, based on current U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics information.

The fundamental truth is that across all channels, adult bikes aren’t putting any more real dollars into the industry today than they were at the end of the Clinton administration. It’s the same pair of pants; we’re just shuffling the money around to different supplier and retailer pockets.

The mass versus specialty channels question is a little more complex, but the fundamental truth is that across all channels, adult bikes aren't putting any more real dollars into the industry today than they were at the end of the Clinton administration. It's the same pair of pants; we're just shuffling the money around to different supplier and retailer pockets.

So, despite the well-earned success of a few large brands, the overall bike market is as stagnant as that water bottle full of energy drink you forgot to rinse out last month. In marketing terms, that means if brands want to grow, the only realistic way to do so is to capture market share from the competition. And guess what: you just can't do that with a product-focused approach in a mature sector, where products are all pretty much at parity. And especially not by waiting around for the "next mountain bike" to show up, or by being first to market in the micro-niche du jour. We've been reading from that same tired old script for almost 40 years now, and the brands who can successfully flip it will be the ones that succeed and ultimately dominate in the next decade.

Creating success in a flat market

I was talking with QBP president Rich Tauer a couple weeks ago about brands and how they work in the bicycle business. He said three really wise — and increasingly important — things.

The first was, "People aren't just buying a bike; they're buying a brand, and they're buying the attitude that comes with that brand." That makes complete sense in a market where products are distinguished primarily by either small personal-preference level features or by price, and I think we as an industry know that.

The second was, "The core of the brand's success is the experience the consumer has with the retailer." This is an important point because, while it's regarded as a gold standard in other consumer product industries, it's almost unheard of in the specialty retail channel bike business. Suppliers make the units and splash out marketing cash, but actually closing the sale is left to the retailer. (We can talk about Click & Collect dealer end-runs another time.) And retailers are rewarded according to share of units on the shop floor and number of units sold, not according to the customer's experience purchasing that brand.

But the third item Rich mentioned is what really split things wide open: "Trek is way ahead in this regard. Specialized hasn't shown the same appetite for it, and neither has Giant or Cannondale." And in my experience, he's right about that, too.

The conversation drifted off into other areas, but I'd like to unpack these ideas a little in the context of script-flipping.

Some brands are doing a much better job creating and nurturing a positive customer experience with their retailers than others. That's a huge opportunity for other brands that want to get ahead in this flat market.

Now here's some tough news: cyclists in general think that bike shops in general pretty much suck at customer service. What matters here is not whether that's objectively true, or whether it's getting better or worse, but whether that's the perception right now. And it absolutely is.

If you haven't done so already, I encourage every person who makes their living in our industry to read this infamous Bicycling story by Gloria Liu from last month. You probably won't like it, but you need to read it anyway.

Frankly, I support Liu's position. She's saying: 1) Here's a problem some cyclists have reported with some shops. 2) Here are some other shops doing an exceptional job of taking care of their customers. 3) Cyclists owe it to themselves to take their business to shops that treat them right.

But here's my larger point: Bike and equipment brands compensate a retailer who delivers a horrible customer experience exactly the same as the one who delivers an outstanding one.

And that's absolutely crazy.

That crappy shop that gives away its margin with discounts can move more units than the one that holds to MAP and helps customers fall in love with your brand, but at the end of the year or the decade, one will have helped build your brand while the other has helped destroy it.

If nothing else, which shop is doing a better job of supporting the brand and ultimately creating lifetime customers for it? Number of units sold per year won't necessarily show the difference. That crappy shop that gives away its margin with discounts can move more units than the one that holds to MAP and helps customers fall in love with your brand. But at the end of the year or the decade, one will have helped build your brand while the other has helped destroy it.

Which is why I say it's time for us to flip the script from focusing exclusively on pushing units through the sales funnel to caring more about winning and keeping lifetime customers. And that means brands need to reward the retailers who help them create customer lifetime value.

As to how we do that, there are a number of best practices established and proven in other industries. I'll be discussing them in Part Two.