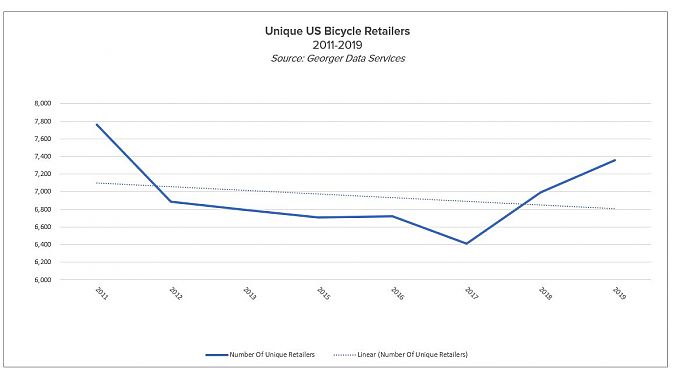

In BRAIN’s April 1 issue, BPSA executive director Ray Keener wrote a pair of pieces, Just how many bike shops are there, anyway? and Is the number of shops shrinking? Both articles are based on conversations with industry consultant and self-described “data wizard” Christopher Georger and his company, Georger Data Services (GDS). GDS maintains a database of more than 7,000 U.S. bicycle retailers based on bike brands’ dealer lists.

As it happens, I interviewed Georger around the same time as Keener had spoken to him, but my queries led in a different direction. I am less concerned with the total number of bike shops than I am with 1) what those seven thousand bike shops mean for the industry, 2) whose bikes are in those shops, and, ultimately, 3) what it means to be a shop in the Bike 3.0 era.

All your base are belong to Tier One — well, 53% of them, anyway

Let’s begin with how Georger’s company divvies up the market. According to his methods, there are three categories of brands, which he and I have agreed to call tiers. Note that tiers are not defined by unit or dollar sales, but by the number of unique shop locations on their dealer lists ... with some important caveats, as we shall see.

I am less concerned with the total number of bike shops than I am with 1) what those seven thousand bike shops mean for the industry, 2) whose bikes are in those shops, and, ultimately, 3) what it means to be a shop in the Bike 3.0 era.

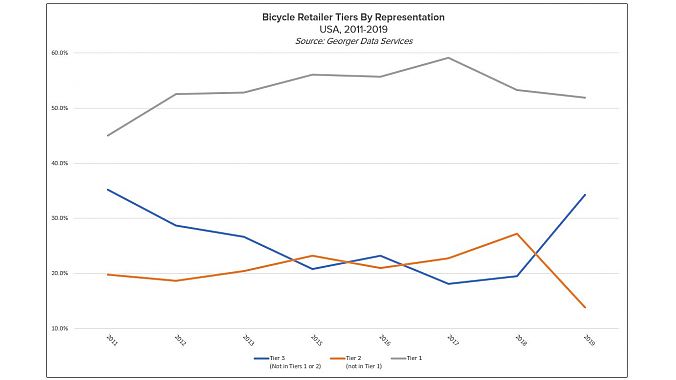

GDS counts a total of 7,354 bike shops as of March 2019. Within that number, here’s how the tiers stack up.

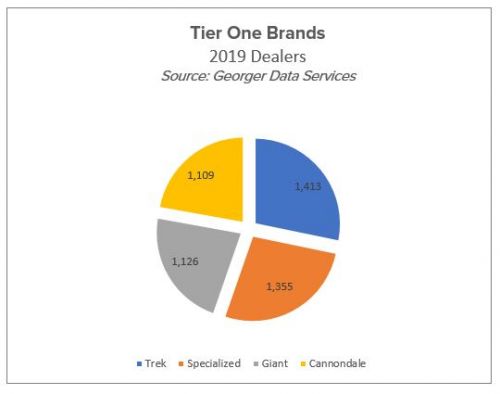

Tier One is the four industry leaders — Trek, Specialized, Giant and Cannondale — in order of number of dealers. Note that Trek’s numbers do not include Electra, nor do Cannondale’s include the various other CSG brands. Tier One brands have been the same four players, in the same order, for as long as Georger has been keeping count, which goes back to the mid 2000s. Total dealer locations for these brands as of March 2019 is 3,817, representing more than half the total number of retailers in the United States (53% on historical average). To be clear, that means more than half the bike shops in the US sell Trek, Specialized, Giant or Cannondale.

More than half the bike shops in the US sell Trek, Specialized, Giant or Cannondale.

Individually, the Tier One brands’ dealer counts look like this: Trek, 1,413; Specialized, 1,355; Giant, 1,126; and Cannondale, 1,109.

Astute readers will be quick to point out that those numbers add up to 5,003, which is more than the 3,817 total stated earlier. Readers who are even more astute will realize this is because there are some retailers who carry both Trek and Specialized (261 of them, according to GDS), or some other combination of the four brands.

Tier Two represents the next six brands’ unique dealers (“unique” meaning retailers that carry one or more Tier Two brands, but none of the Tier One brands). Alphabetically, these are currently Cervélo, Electra, Felt, Kona, Santa Cruz and Scott. These brands share a collective count of 1,018 unique retailers. And as before, there is overlap among them, and (of course) there are Tier One retailers who also carry brands from Tiers Two or Three.

Membership in Tier Two is relatively fluid, with new brands entering (Cervélo, Kona and Santa Cruz in 2019) and others leaving it at various times (Raleigh in 2017 and Fuji in 2018, for instance).

Tier Three retailers are those who do not carry any of the top 10 brands listed in Tiers One and Two; they represent 2,519 retailers out of our 7,345 number. But again, there are lots of Tier Three brands represented in Tier One and Two shops, too.

As examples, Tier Three brands include Blue Competition, BMC, Breezer, Fuji, Haro, Ibis, Intense, Jamis, KHS, Linus, Marin, Mirraco, Masi, Niner, Norco, Orbea, Performance, Pinarello, Pivot, Pure, Raleigh, Rocky Mountain, Salsa, SE Racing, State, Van Dessel, and Yeti. Of course there are others.

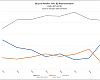

The chart at right shows dealer share by brand tier over time as a percentage of total number of retailers. Since 2011, Tier One has grown overall, but it’s more difficult to interpret what’s happening with Tiers Two and Three. The drop in Tier Two dealers since 2018 may be a result of Tier Three brands becoming stronger, but it’s more likely an artifact of changes in the lists themselves (more discussion on this farther down the page) and the entry of a new wave of Tier Three brands, especially among Pedego and other e-bike labels.

A Quantum Theory of bike shops … sort of

All of this means the GDS list is not literally a list of bike dealers, but more accurately a refined, collated and integrated list of other lists. Calling it a quantum theory approach to bike shops may be a bit much, but as with a scientist and subatomic particles, Georger can’t see the actual objects he’s studying; he can only infer their existence by how they interact with other, observable phenomena. To switch metaphors, it’s a two-wheeled version of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave.

To his credit, Georger never claims his numbers represent anything other than this. And, as we shall see presently, the distinction becomes pivotal as we try to answer the question of how many bike shops there are and ultimately, what defines a bike shop in the first place.

How many brands are on the GDS list? “Everything from Assos (he tracks some equipment brands, as well) to Transition and Van Dessel and Yeti,” Georger says. “More than 100 bike brands. 90% of the IBD brands.” Pressed for detail, he says he has tracked 134 different bike brands over time, including 58 “important significant meaningful ones,” which he updates most frequently.

Probe a little deeper and Georger points out he hasn’t done Dahon in years, for instance, or Tern ever, because “they also sell to mobile home parks and RV dealers, all kinds of places that aren't bike shops." He also omits “small co-ops in small cities run by volunteers selling used bikes.” And, significantly, there’s an ever-increasing number of electric-only brands as the category heats up, including more than 100 Pedego dealers.

A bike brand is a bike brand if other bike brands say it is.

There are various methods of getting to the data in those lists. Client brands share their own data with him, and the rest, well, the rest is a trade secret. Or at least it’s a secret unless you’re aware of a common online technique called “data scraping,” a topic on which Georger declines comment. I’m not here to bust his chops on his methods, merely to point out that these methods exist and at least the good ones are both reliable and proven.

So which brands does he consider important/significant/meaningful and which does he track? That’s easy: the ones his clients pay him to. But when asked who those clients are, Georger demurs, citing client confidentiality and non-disclosure agreements. Which means that to Georger Data Services, a bike brand is a bike brand if other bike brands say it is, and at least one of his clients is willing to pay GDS to track it. And a bike dealer, perforce, is whoever those hundred-odd bike brands say is one.

Personally, I’m OK with that, as long as the core client list represents some kind of critical mass of important brands the industry itself regards as legitimate. There are worse things than consensus.

When is a bike shop not a bike shop?

In the old days it was easy. You had a storefront, you sold IBD-quality bikes, you were a bike shop. But the rise of high-end sporting chains, brands duking it out for limited floor space with successful retailers and being forced into other channels, entry of new brands and retailers, and the invention of something called the internet has changed all that.

Enter Christopher Georger and his decidedly agnostic approach to defining what a bike shop is. And not everyone likes it.

Detractors point to four major issues with GDS’ dealer list-based approach. These all involve questions of factual accuracy and definitions:

Dead or nonstocking dealers. Like your late uncle on Facebook, shops that have ended a relationship with a brand or gone out of business entirely can live on for years on dealer lists. Georger is stubborn on this point. “I don’t count bike shops,” he insists. “I count unique locations on dealer lists and filter out the duplicates.” But it’s not just about shops going out of business or switching brands. Consider these examples:

- Raleigh stopped publishing a dealer list in 2018, so its retailers are no longer captured in Georger’s data, although some still show in his list. (Also, most Raleigh dealers also sell other brands, so they’re picked up that way.)

- Conversely, Huffy’s specialty retail brand Batch claims 5,896 dealer locations (zoom out on the map using the minus option to see this). Note there is a disclaimer at the bottom of the linked page, “Batch Bicycles are not sold at all of the specialty retailers listed above.” A separate flag on the map indicates locations Batch claims as stocking retailers; I hand-counted a total of six in Southern California from Santa Barbara to the Mexican border. Are the other thousands of locations Batch dealers or not? Draw your own conclusions. (Note Georger does not include Batch among the brands he tracks.)

- Haro Bikes, which according to Georger, purged more than 1,000 locations from its dealer list over a 12-year period. “In 2007, they showed 1,861,” Georger says, “by 2019 they had 730.” In general, Georger believes, published dealer lists have become more accurate in the time he’s been working with them.

- A final example would be Performance bike shops, which are all currently in limbo, but still show on various brands’ lists, and therefore on Georger’s.

Basements and garages. Are all the locations shown “real” bike shops? Not my problem, says Georger. If a brand lists a location as selling its product that’s “real” enough for his purposes.

Chain and online stores. Among many other examples, REI sells Cannondale in most if not all its stores, and Electra in 139 locations. 27 Scheels stores sell Trek bikes. Gander Outdoors (formerly Gander Mountain) sells Fuji. In the purely online space, Competitive Cyclist sells Bianchi, Santa Cruz, Ibis and Yeti. Jenson USA sells Santa Cruz, Ibis and Yeti plus Niner and Jamis. Other examples are too numerous to count. None of this is either good or bad; it is simply the way things are.

Mobile dealers. Is a mobile bike shop a bike shop, even if it maintains no inventory? According to Georger, it is if it fulfills sales for a brand and is listed on that brand’s dealer list. (Note also that the former brick-and-mortar-only NBDA is now accepting mobile dealers as members, according to NBDA president Brandee Lepak.)

Ultimately, what’s changed is not just the number of bike shops, but our entire collective definition of what a bike shop is.

In terms of literal accuracy, the most definitive lists are the ones kept by the largest bike brands themselves, which in many cases use GDS’ data as a starting point. These brands have the outside reps to physically check every street address on a list, and the inside staff to go to every website and confirm the bikes represented there can be ordered and booked for shipment.

But none of these brands are likely to share that hard-earned data with the rest of us.

Ultimately, what’s changed is not just the number of bike shops, but our entire collective definition of what a bike shop is. And that means we need to change how we count those shops. No method is perfect. But until someone comes up with that perfect method, I’m on record here as saying Christopher Georger’s model and a working number of 7,000-ish bike shops to it as we’re likely to get.

[Editor's note: Just to be clear, the 7,000 number, as with most of those cited in this article, counts bike shop locations, not owners. So Erik's, for example with about 30 locations, is counted about 30 times. One major distributor recently told us that if you count owners, not locations, there are about 5,400 in the U.S. who qualify for an account.]

Yes, it’s messy. And, to some extent, arbitrary. But guess what. This is the bike business, and we ought to be used to that by now.