In Part One of this series, we established that, thanks largely to sensationalist media, the public has a horrifying perception of bikes as two-wheeled death traps. Part Two explored the industry's significant-yet-largely-unacknowledged loss of both riders and revenues over the past 15 years. These events may or may not be causally linked, but it's hard to escape the logic that blood-soaked media reports lead to fear of bicycles, which leads to fewer bicycle riders and, consequently, fewer bicycle sales.

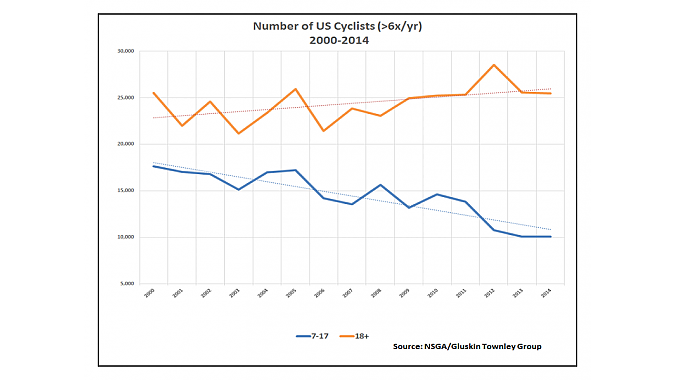

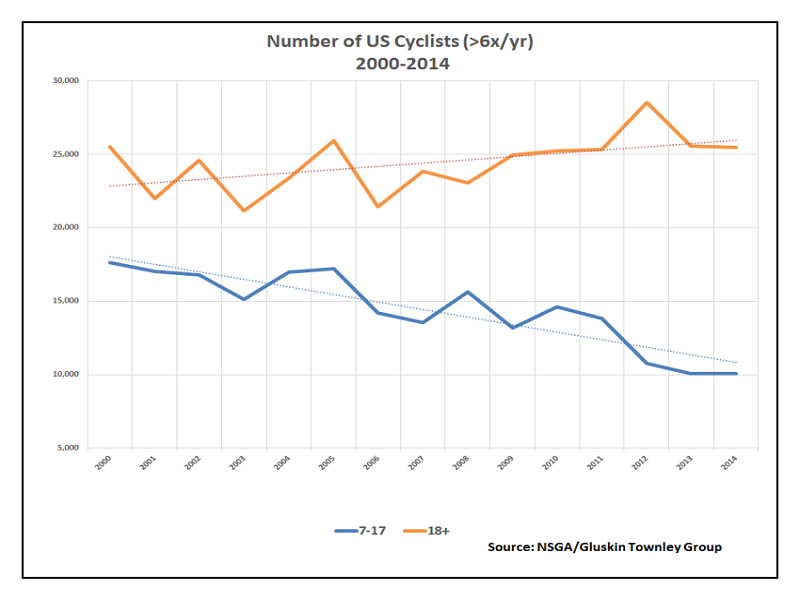

Here in Part Three, we'll talk about what we might do about to deal with the stigmatization of bicycles, and the industrywide loss of revenue. But first, let's look at where the ridership losses in originate. Below is a graph similar to the one from Part Two, but this time with the riders broken out by age.

The good news is, the number of adult riders (orange) has remained surprisingly stable; it's even trending up slightly. What's disturbing is the under-18 segment (blue) has plummeted from almost half the youth population (43.6 percent) in 2002 to just over one-fifth (27.4 percent) 19 years later, a net loss of more than one-third (37 percent) of young cyclists.

In the short term we can reason that the overwhelming majority of these lost sales would have gone to mass-market vendors and do not directly impact the specialty retail market. But in the long term, this is the market segment our future customers will come from as the current market segment ages.

We can blame video games for the fact that our kids aren't riding bikes. We can blame television, just like our parents did. We can blame lurid media accounts and overprotective parents. Or we can blame ourselves. Whatever the real culprit is, here's my response: I don't care. What matters is what we're going to do about it.

Given the evidence, it becomes obvious that Job No. 1 is to ensure that as the baby boomer generation gets older and hangs up its bikes, there is a young generation of bike-riding customers ready to take its place. And to do that, we have to convince not just kids, but their parents, that riding bikes is safe, fit and fun.

We'll go into the how of this in just a minute. In the meantime, let's look at another graph.

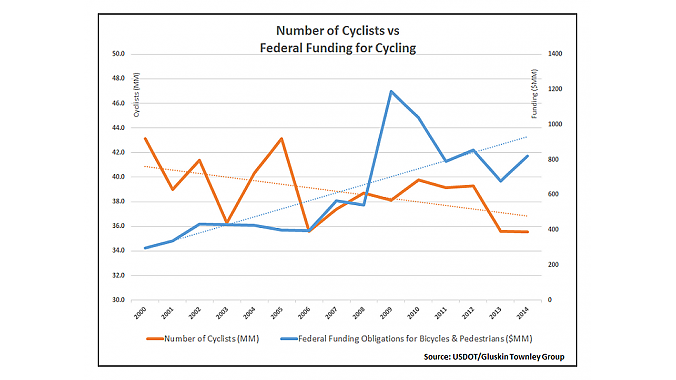

Famously launched by John Burke, Mike Sinyard and about a hundred industry attendees over an Interbike breakfast in 1999, Bikes Belong (now PeopleForBikes) has long been a prime mover in the bicycle advocacy world. While it sponsors some ridership programs (the National Bike Challenge, for instance) PeopleForBikes' primary focus has been securing funding for advocacy groups, programs and the creation of cycling infrastructure, including bike lanes and paths.

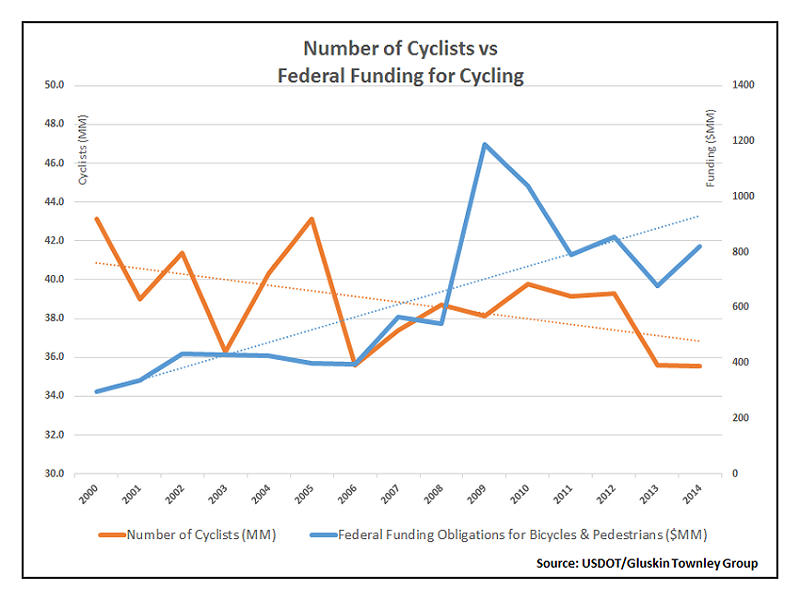

The graph at right shows the familiar orange line with the decreasing number of cyclists (whom we now know to be mostly kids) juxtaposed with increasing federal funding commitments (blue) for cycling and pedestrians during the same time frame.

Clearly, there is zero correlation between funding and ridership.

While traditional advocacy has been successful at obtaining resources for bicycles and infrastructure, the numbers show funding and, by implication, infrastructure have not translated into more people on bikes more often — or more people riding more bikes.

So if Job No. 1 is to brand cycling as safe, fit and fun — especially for young people — close behind it is Job No. 2: the need to get entire families out having fun on bikes, taking advantage of the infrastructure we've been successfully building for the past 16 years.

Fortunately, the two work together. If we accomplish Job No. 1, Job No. 2 will follow; if we can get families on bikes, they'll bring the kids. So let's break it down.

Safe means we have to expose the media lies about the dangers of cycling and replace them with more positive messages. This is largely a PR challenge. For every story about cycling danger, we need a story about cycling benefits. And "stories" means print and Web stories, broadcast news, and "soft" news like social media, talk shows and community features.

Safe also means we have to danger-proof riders, especially kids. Fortunately there is already a model in place. Through the Motorcycle Safety Foundation, the motorcycle industry is doing an excellent job of counteracting motorcycles' reputation as dangerous vehicles with public safety classes that emphasize situational awareness and risk management instead of rote skills training. The programs are administered in conjunction with state police, DT or highway patrol organizations.

For our industry, the problem with past bicycle safety courses has been that it's hard to draw attendees: How can kids participate in riding classes when they don't even have bikes? And why would they care about bicycle safety when they don't ride in the first place?

Two answers. We create demo fleets of moderately priced (but nonetheless far better than department-store grade) loaner bikes, and we help schools or community organizations create safety programs with assistance from groups already in place like Trips For Kids (with dozens of growing chapters in the U.S. and Canada), or Safe Routes To School (with programs in all 50 U.S. states).

Best of all, if we can defuse the notion of bikes as certain death on two wheels, program attendance will get a huge boost from parents. Because once bikes are safe, bikes offer a solution to a huge problem almost every parent wrestles with.

Fit means we promote the health benefits of cycling at a national level, using the same PR resources we put in place for the Safe message. With childhood obesity rates hovering near 20 percent and adult obesity at more than a third, we focus on cycling's fitness benefits. The two-part message is, we can make you and your kids safer on bikes; we can make you and your kids fitter with bikes. And, if we can convince parents that cycling makes their kids less fat, they'll be pounding on the doors of local bike shops nationwide.

Fun is easy. Bikes are just plain fun to ride, and almost everyone's initial bike ride finishes with a big smile. But we need to do more to encourage people to make more of those fun initial rides in the first place.

Since 2005, the Recreational Boating and Fishing Foundation (RBFF) has run a robust and successful program, Take Me Fishing, to promote its activities. Take Me Fishing does exactly what the bike industry needs to do: gets adults back into boats (or, for us, onto bikes) to take kids fishing (or cycling) on a family basis.

The final element to promoting family cycling is that we need to make bikes hip again. Not just for the skinny, Lycra-clad boomers and Gen Xers who are currently the target audience for 95 percent of all bicycle advertising and promotion, but for millennials. These 15- to 32-year-olds are already abandoning cars in record numbers in favor of bikes and/or public transportation, so they're perfect role models for the audience currently at greatest risk, Generation Z (post-millennials).

But we have to get the bikes-are-hip/bikes-are-fun image planted firmly in the minds of these young audiences. This can be done through any number of mechanisms, but the most cost-effective, in marketing terms, might be product placement in movies and television (remember Jerry Seinfeld's Klein?). Happily, that's another thing PR agencies excel at. And placement costs for movies and TV in noncontested categories like bicycles are still in the very reasonable four-figure range, depending on the production.

So, how do we fund all this stuff? The Take Me Fishing initiative, for instance, had an operating budget of $13 million in 2014, of which $12 million went directly into engagement programs. The bicycle business has not traditionally had access to that kind of money.

But these would be nontraditional programs, and we need think about funding them in nontraditional ways.

By way of benchmarking, the total operating budget for PeopleForBikes in 2014 was just over $7 million. On the other hand, combined global outlay by U.S. bike companies for Tour de France racing teams in 2015 was in the neighborhood of $100 million in cash, bikes and equipment.

No, I'm not proposing to gut PeopleForBikes (or even Tour de France teams) to make room for cycling education and promotion programs. But if we don't get together as an industry to figure out what we're going to do about it, there is good evidence that the next generation of riders will be a fraction of the size of the current one.

Maybe it's time for another breakfast meeting.