By Rick Vosper

This is Part 1 of a two-part series exploring the new market dynamic for the specialty retail segment, how we got there, and how the industry can respond and adapt to the new reality. This section is primarily focused on the “how we got where we are today” part of the story.

I note there is plenty of room here for alternative points of view and frankly, I expect a lively discussion.

Bike 1.0: When Schwinn Ruled the Earth

What I’m calling the 1.0 era is the postwar period of relative stability from 1950-75 (more or less). A single market leader, Schwinn, effectively controlled much of both the supply and retail sides of the specialty business channel. Schwinn had a well-organized, well-managed and marketed, vertically integrated supply chain based on domestic production. At the same time, it created, nurtured and maintained a strong network of semi-independent retailers.

The resulting dynamic was a largely stable market and birth of what we would now recognize as the modern independent bicycle retail landscape. But Schwinn’s efforts were so successful the company was subject to a restraint of trade lawsuit in 1957, dragging on for 10 exhausting years. As a result, Schwinn abandoned its system of independent wholesalers/distributors, moved to an in-house distribution model and lost much of its control of retailers. (More about the lawsuit and other topics are available in the very thorough Wikipedia article on the history of Schwinn.)

Nevertheless, stability continued though the Bike Boom of the early to mid-'70s and the death of Bike 1.0 as Schwinn’s control inexorably declined as the result of a changing situation it failed to adapt to.

Bike 2.0: End of the Bike Boom, Rise of the Mountain Bike, and the Era of Perfect Competition

During the Bike Boom, lightweight drop-bar imports had already claimed significant market share and with them, increasing power for their independent importers/distributors. The trend continued and accelerated even as the boom turned to bust, with the initial introduction of quality Asian bikes, originally from Japan and later, as value of the yen climbed, from Taiwan and eventually mainland China.

In parallel, a new era of U.S. manufacturing of high-quality bikes from companies like Trek and later Cannondale began to affect the market. The table was already set for the mass introduction of mountain bikes in the early 1980s and all that came with them.

The mountain bike’s success was not merely based on an exciting new product category, but on a new generation of leaner, more agile brands and an entirely new business model, one largely powered by Asian-based manufacturing and finance. Trek, Specialized, Giant, Cannondale, Shimano and every other major industry player today came of age during Bike 2.0.

It was also the Golden Era of the American independent bicycle retailer, eventually peaking at more than 6,100 shop locations (“doors”) in 2001 at the dawn of the 3.0 era.

With the increase in independent retailers and new brands, and fueled by the explosion of mountain bikes and cyclists hungry to purchase them, Bike 2.0 was a wide-open, Wild West-style marketplace. To be sure, by the mid-1990s a few brands (notably Trek, Giant, Cannondale and Specialized, in that order) were growing stronger and the market was beginning to stabilize. But the most notable dynamic was that of perfect competition — very broadly, a situation where no one brand or brands can achieve enough share to dominate and thereby control the market. Profits are low throughout the supply chain, and consequently both brands and retailers lack resources to overcome the inertia of a perfectly competitive market.

Bike 2.0 was a wide-open, Wild West-style marketplace

The concept of perfect competition is core to the Bike 2.0 phenomenon. There are different definitions, but classically, a perfectly competitive market has four requirements:

- A large and homogeneous market. There are relatively large and ongoing sources of supply and demand, and relatively little differentiation of brands or products. For the bike business, this was a time when bikes were defined in the brands’ own marketing literature by the Shimano component group bolted onto them.

- Information availability. Consumers know what every brand costs. True with the publication of consumer buyers’ guides and “brand bibles” — and even truer with the advent of the internet in the mid-'90s and beyond.

- Absence of external controls/low barriers to entry. Governmental regulation, limited resources, price controls or lack of capital do not affect the market or prevent new players from entering. Pricing is (relatively) uniform across brands and competing models.

- Cheap and efficient transportation. Transportation costs do not create price or brand differentiation. Moving containers of bikes from Asia and around the United States was cheaper than domestic production, and more importantly, all brands’ costs were about the same.

For all this, the mountain bike and post-mountain bike eras were times of rapid innovation, with new designs and ideas cropping up literally every few months — indexed shifting, clipless pedals, titanium and carbon frame and component materials, suspension systems, disc wheels, aero bars for road and bar extensions for mountain bikes, the rise of cycling eyewear and nutrition products — literally hundreds of new developments, many of which still collectively define the current market.

But with notable exceptions like Dia-Compe/Cane Creek’s Aheadset, not one of these new ideas created a sustainable competitive advantage for their inventors because they were easily imitated and absorbed back into the perfect competition maelstrom. Conversely, the sheer rate of innovation made it difficult for any single brand or group of brands to achieve enough market traction to gain ascendancy.

As the mountain bike and then suspension mountain bike markets faded in succession at the turn of the century due to saturation, something had to give. And something — three somethings, in fact — did.

Welcome to Bike 3.0

By 1998, the industry was in contraction. “Flat is the new up,” pundits chirped (in real terms, it was more like “Down is the new flat.” In 1999, Bicycle Retailer summed up the industry’s malaise with a chilling three-word headline: “Doom and Gloom.”

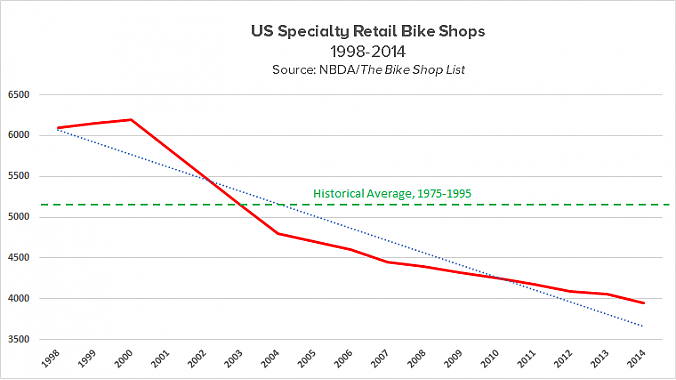

The contraction hit retailers hardest and first. With a historical average of just over 5,000 storefront locations between 1975 and 1995, the number of independent bicycle retailers (as defined by the NBDA) plunged from more than 6,000 in 2001 to 4,800 just three years later, a net loss of 1,300 storefronts or more than 20 percent net.

The contraction hit retailers hardest and first. With a historical average of just over 5,000 storefront locations between 1975 and 1995, the number of independent bicycle retailers (as defined by the NBDA) plunged from more than 6,000 in 2001 to 4,800 just three years later, a net loss of 1,300 storefronts or more than 20 percent net.

In 1999, Bicycle Retailer summed up the industry’s malaise with a chilling three-word headline: “Doom and Gloom”

The number continued to decline, dropping steadily for the next decade, to fewer than 4,000 retail locations in 2014, at which point the NBDA literally stopped counting.

The current number of survivors under the NBDA definition is unknown. Other sources, which include sporting goods stores, businesses like the now-insolvent Performance chain and less traditional entities in their estimates, put this number much higher.

The surviving retailers almost by definition are smarter, more agile and more efficiently run businesses

So the first defining characteristic of Bike 3.0 in the new millennium is a finite and presumably declining number of dealers, with more than a third of locations lost over a period of 15 years, and probably more since. The flip side to this is that the surviving retailers almost by definition are smarter, more agile and more efficiently run businesses with streamlined processes and better inventory turns. This is confirmed by the NBDA’s own Cost of Doing Business reports.

Instead of simply opening more retail locations, brands had to focus on creating strategic alliances with selected dealers and controlling as much floor space (and therefore, purchase budgets) as possible. (Much) more about this in Part 2 of this series.

The second defining characteristic is contraction and consolidation at the supplier side of the business. This began during the decline of Bike 2.0 in the 1990s with the demise, resurrection and subsequent consolidation of Schwinn and GT under various owners and currently under Dorel; Specialized’s disastrous acquisition of Monolith and short-lived partnership with Ritchey; the various equipment brands and sub-brands of Bell/Giro/Easton and others; Trek’s acquisition and integration of Fisher, Klein, LeMond and Bontrager; and the ill-fated consolidation of Raleigh USA and True Temper along with non-cycling businesses under the now-defunct Huffy umbrella.

The trend continued — and continues today, and doubtlessly will continue to continue in the future — into the new millennium and the Bike 3.0 era. More recent examples include Trek’s acquisition of Electra, Felt’s acquisition by Rossignol and Mavic’s acquisition by Amer Sports; SRAM’s consolidation with Sachs, RockShox, Avid, Truvativ, Zipp et al; Pon’s acquisition of Cervélo and Santa Cruz; the emergence, growth, consolidation and now bankruptcy of Fuji/Breezer/Kestrel/Performance by ASI/ASE; Raleigh’s acquisition and rumored pending sale by Accell Sports; and many, many others.

Still other brands too numerous to mention have failed outright and disappeared from the industry radar without a trace as fast as they entered it.

Third and finally, Bike 3.0 is defined by the rise of internet commerce, and with it the integration and subsequent disintermediation of once-discrete global markets and sales channels. Again, examples are both well-known and too numerous to mention here.

None of this is either good or bad. It is simply the way things are. As an industry, we either accept the new reality or ignore it at our peril.

Next time we’ll explore the effects, market dynamics and strategies of doing business in the era of Bike 3.0, and two more potential disrupters just now beginning to affect the industry.