By Alan Coté

A version of this article ran in the September issue of BRAIN. After the print article was published, the patent was granted.

(BRAIN) — Trek Bicycle is getting highly analytical when it comes to how bicycle rims slice through the air.

While wind tunnels and judicious engineering of composite materials have been used for decades as part of bicycle wheel development, a new patent application from the Wisconsin company ups the development game to a new level.

In August, the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office granted Trek’s utility patent, 2019/0213785, “SYSTEM AND METHOD FOR RIM SHAPE DETERMINATION.”

In it, Trek claims intellectual property that’s computer-based, with parameters including computational fluid dynamics, pareto fronts, and more. This is a bike industry patent application that gets Silicon Valley-deep in the mathematical weeds.

It’s very likely that bicycle retailers, riders, pro teams, etc. will never be aware of this technology. Indeed, the invention is applicable only to engineers working on the bleeding-edge of high-performance bicycles — but the intrigue is that it’s a tool with the potential to rapidly advance wheel design.

And it’s intriguing that Trek, which declined to comment for this story, is investing in this type of abstract R&D work.

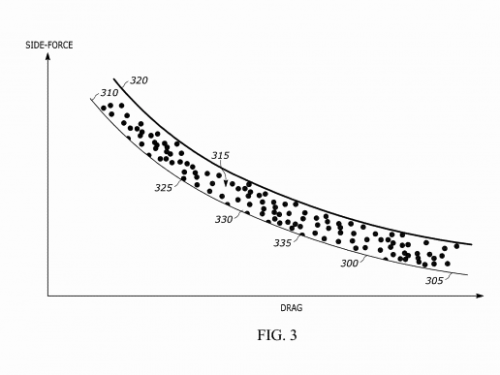

A brief invention overview: In the simple version, rim width and depth are provided, and the system uses computational fluid dynamics to generate an optimal rim shape — one that minimizes drag, as well as side forces that affect stability. A more complex version includes software that develops a pareto front — an engineering approach that seeks best outcomes of multiple combinations of choices.

Some of those additional choices discussed include the curvature of a rim’s sidewall, the interface of tire and rim, and more. For example, make the rim deeper in cross section, and that may lower drag, but also decrease stability. Change the curvature of the rim’s cross-section, and the drag and stability may also change. The pareto approach seeks the best combinations.

What does this mean for anyone who isn’t a bicycle wheel engineer? This technology looks to accelerate wheel development and reduce R&D costs. Consider the primitive, iterative approach: design a rim, make a few expensive prototypes, and then test in the wind tunnel and on the road.

This invention allows much of that to occur virtually — though of course, the resulting designs still need real-world testing. Trek’s approach could in principle streamline (oh, yes!) the design process for its Bontrager line of wheels, allowing optimal rim shapes to be much more easily identified, whether for road, gravel riding (and their seemingly never-ending increases in width), or time trial/triathlon uses.

It is somewhat puzzling why Trek decided to pursue a patent on this, rather than keeping it a trade secret. A patent requires full disclosure of how to make an invention in exchange for exclusive rights, whereas with a trade secret, a company keeps details hidden from outsiders. It seems almost impossible for Trek to detect if one of its competitors were copying this approach, as the invention is a computer process used by only a handful of engineers.

The application lists the inventors as Claude Drehfal and Mio Suzuki. According to LinkedIn, Drehfal is an engineering intern at Trek, while Suzuki has moved on to become a senior R&D engineer at Specialized.

Most industry patents are focused on bike parts, like the many patents covering excruciating small nuances of chain links. This type of computer-based patent application is an indication that the bicycle industry is stepping into new engineering territory.

Alan Coté is a Registered Patent Agent & principal of Green Mountain Innovations LLC. He’s a past contributing writer to Bicycling, Outside, and other magazines, and a former elite-level racer. He also serves an expert witness in bicycle-related legal cases.