Editor's note: This article appeared in the January 1 issue of Bicycle Retailer & Industry News.

CUPERTINO, Calif. (BRAIN) — Many customers who walk into mountain bike retailer Trailhead Cyclery ready to buy their next bike have researched and compared brands, models and spec. They know what color, build kit and tire size they want, and how much they're going to spend.

But even though — or maybe because — they've pored over geometry charts, measured their existing bike and done some test rides, many of these savvy shoppers still need help finding the right size.

"There is an enormous amount of dollars being spent and hyper attention to details. So there is consternation about buying the wrong thing," said Trailhead owner Lars Thomsen. "Most of the conversations I have with riders choosing their next bike usually involve fit."

While progressive geometry like slacker head angles, steeper seat tube angles, longer toptubes and shorter stems has made modern mountain bikes more comfortable and confidence-inspiring to ride, fitting riders to these frames isn't as straightforward as it used to be. And looking at geometry charts can sometimes create more questions than answers.

For one, toptubes are longer than ever on most modern mountain bikes, so that measurement has become all but irrelevant when it comes to sizing. Instead, many manufacturers emphasize the reach, or the horizontal distance measured from a vertical line drawn through the center of the bottom bracket to the center of the headtube, a number that is not contingent upon geometry differences.

But basing sizing on this number can be problematic because customers tend to consider reach the distance between the nose of the saddle and the bars — which does change as geometry, namely the seat tube angle, changes.

As seat tubes have gotten steeper, the distance between the saddle and bars in many cases is shorter, which can make longer-reach bikes actually feel shorter. Because of this, some riders, no matter how long the toptube, feel cramped.

"The front of the saddle to bar changes with seat tube angle, but actual reach, what the industry is calling reach, from bottom bracket to headtube, does not," said Brian Blair, buyer at mountain bike retailer The Path Bike Shop in Orange County, California. "If they're looking at a chart and think, 'Well, my old bike has a reach of 200 but this new bike has a reach of 240, that's going to be really long.' But then they get on it and they feel cramped. They measure saddle to bars and realize this thing is shorter.

"Bikes are longer. But cockpits are not longer," he added. "Reach is the same no matter the geo, and that measurement worked for a while. Now we've gone far enough and seat angles have gotten so steep, that needs to be factored in."

Getting RAD

Author, coach and skills instructor Lee McCormack believes that focusing on the distance between the feet and hands is a more accurate and better way to size riders to the modern mountain bike. His RideLogic method also takes into consideration that the typical mountain biker is rarely in a static position; riding a bike on trails, especially in technical terrain, is dynamic.

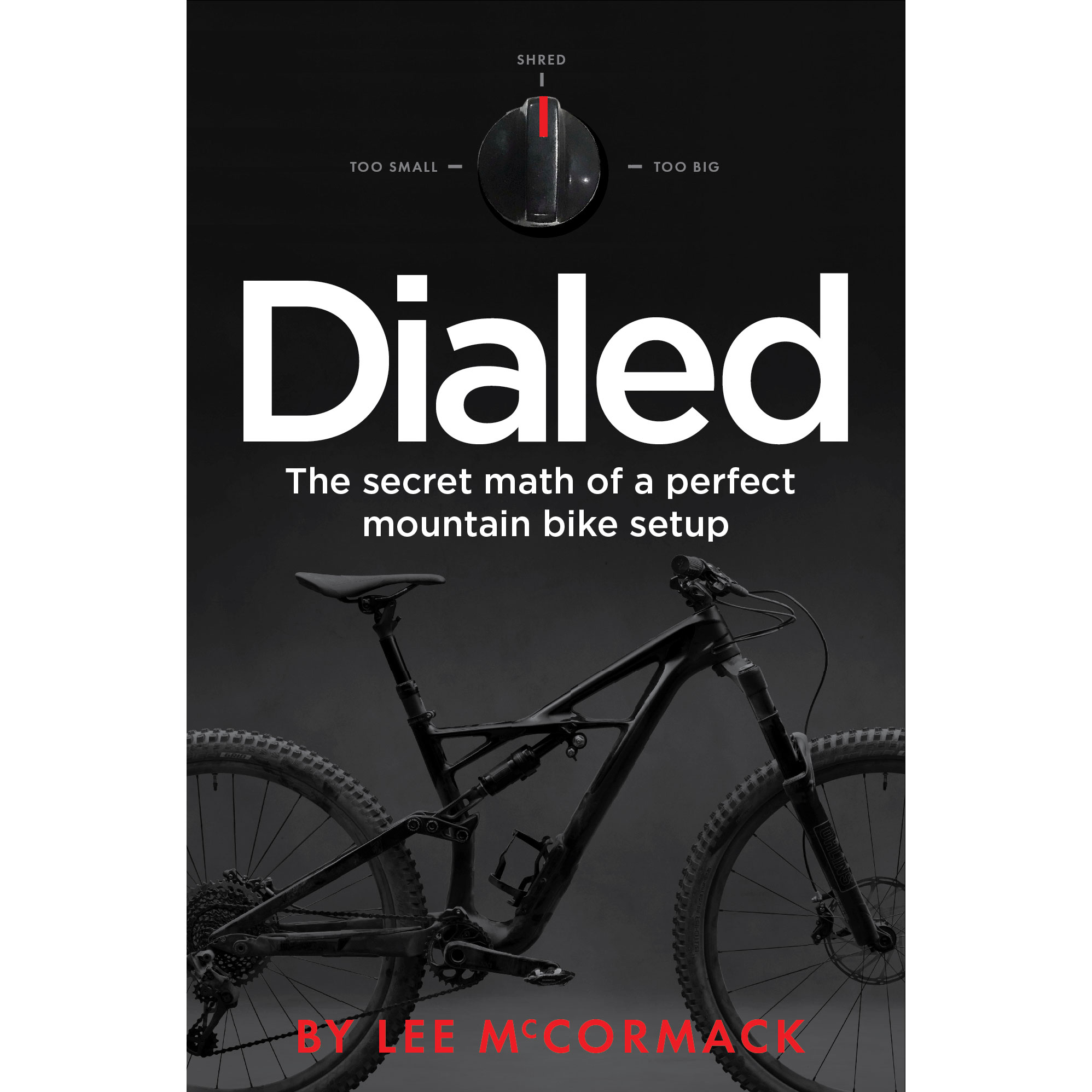

McCormack, who co-authored Mastering Mountain Bike Skills with Brian Lopes, has used RideLogic to fit more than 1,000 riders to their bikes. His method evolved from dialing in his own bike setup to be friendlier to his bad shoulders, and while he has shared it through his online coaching school, seeing so many people riding ill-fitting bikes prompted him to make the method more widely available. With his new e-book Dialed: The Secret Math of a Perfect Mountain Bike Setup, McCormack has made RideLogic available to the public for the first time.

"The fits people get are usually from road bike fitters. That is a problem — they're just not made for dynamic movement. The old way was to start from the feet and set the seat. From the seat, the bars were set. But on a mountain bike, you move a lot and there are lots of angle changes. You move your seat up and down, but the handlebar position relative to the feet stays the same," he said.

Specifically, McCormack's method sets bikes up to get the rider into a perfect position for shredding trails. Determining a person's ideal Rider Area Distance and getting the bike close to that creates the maximum arm range for descending, braking, cornering and dropping, helping the rider access their potential power and optimal range of motion for pushing and pulling.

A rider's RAD measurement is determined by body size and proportion, handlebar width, crank length and pedal and shoe thickness. In his book and on his website, McCormack supplies equations that will work for most people to calculate RAD in millimeters. A rider can measure the RAD of their bicycle by running a string from the top of one grip to the other to create a horizontal line, then measuring from the bottom bracket parallel with the frame to a centerpoint 1 centimeter below the string on the bars. To dial in a bike's RAD, riders can lengthen or shorten their stem and/or raise or lower the stem by adding or removing spacers. As a last resort, they may have to try a smaller or larger frame.

McCormack has also developed the RipRow, a sizing and training tool he has sold to gyms, physical therapists and some bike shops, including Trailhead Cyclery, which uses it mainly to help customers with sizing and fit. The RipRow is an unstable platform equipped with a set of adjustable handlebars that can be pushed and pulled to mimic riding bumpy terrain. If handlebars are at the ideal height, the user should be able to stand up straight with arms straight when the hands are on the grips. That measurement is the RAD, and can be used to find the right size frame.

"I can put a customer on what I think is their right size, but at first they will feel like the bike is too short. Maybe they're used to riding a longer stem or are just used to a size that's too big for them but have been told it's their right size by other riders or have had a professional fit that was geared toward sitting on a seat and being efficient, more of a road-oriented fit," Trailhead owner Thomsen said. "So I say drop the seat and stand on your feet. What does that feel like?

There's not much more that I can do in a parking lot to help them understand or test it out. But I can show them on the RipRow what it looks like and feels like when the RAD is the right length. It's usually enough to convince most riders."

As progressive geometry becomes the norm with more brands introducing models with ultra-slack head angles, long toptubes and steeper seat tube angles, retailers will likely still have some educating and customer convincing to do — after all, this evolution is relatively new. The customer who hasn't upgraded their bike in a few years won't necessarily understand these changes right away.

"The customer with the 10-year-old bike and longer stem will notice that all the stems today are not longer than 50 millimeters, whereas a few years ago you would only see smaller sizes with a shorter stem and that was usually about 70 millimeters, which seems long now no matter what size the bike is," Thomsen said. "And they see the toptube length and think it's way too long, like the customer who comes in and is like, 'Whoa, that SB150 [Yeti 29er] is too long! It's like a limousine.' So you have to explain why the length is better put into the frame than the stem so we're not cantilevering the bike and why the bike might feel small when seated. It's hard to express in words why that's all OK.

"But these geos are better, we're seeing it morph, and we're getting closer to better-fitting bikes right out of the box," Thomsen added.