Hey, guess what. We have too much bicycle inventory. Not just right now (when we have way too much inventory), but in general. That’s because, year after year, we keep ordering too many bikes and then having to put them all on clearance. And this insanity has been business as usual for our quirky little industry ever since the end of the Great Recession in 2009.

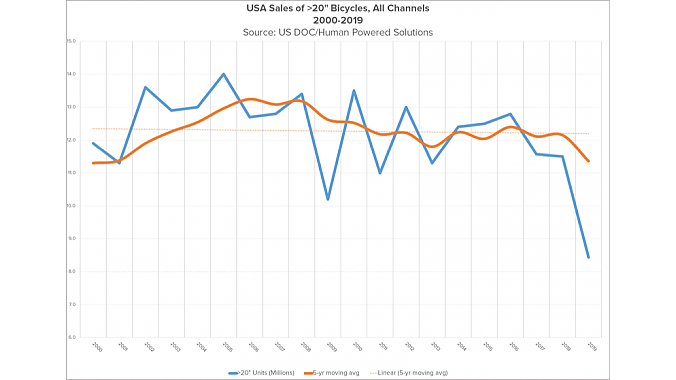

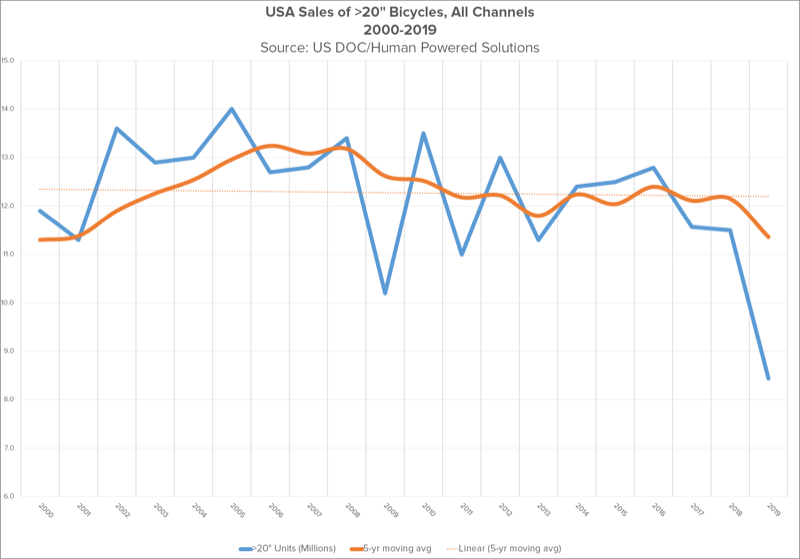

For nine years, from 2010 through 2018, we seesawed back and forth every couple of years between thirteen and eleven million imported units with 20” wheels or larger. And it was always too much. Year after year, we had bicycle inventory offered at discount starting in March or April and continued at discount through September. And then we brought in too much again the next year. Less than the previous year, maybe, but still more than the market wanted to buy. So we had to put it on clearance again that year, too.

I don’t mean to suggest this has been a deliberate strategy on the part of bike brands, but the net effect is the same.

Getting down to scorched earth

The whole basis for twenty years of Bike 3.0 was for leading bike brands to lock down floor space at key dealers in each market, thereby denying their competition access to those dealers.

In military parlance, a scorched-earth policy is a strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. In business, the term usually refers to an attempt to avoid a hostile takeover by making the target company less attractive. I’m using the term here more in the military sense. And what’s the single most useful thing in the bike business?

Dealer floor space, that’s what.

For all the talk of brands turning to D2C sales, the single most effective way for bike brands to sell more product is to put more of it into dealers’ showrooms at lower prices. In fact, as I’ve mentioned many times before, the whole basis for twenty years of Bike 3.0 was for leading bike brands to lock down floor space at key dealers in each market, thereby denying their competition access to those dealers.

One way they’ve accomplished this is by simply producing more bicycles than the market wants to buy. The other is through enforced obsolescence in the form of model years. I’ve been writing on this topic and why it’s a bad idea for more than a decade, as you can see here and here.

As I’ve also mentioned, the Bike 3.0-style scorched-earth policy wasn’t as successful as it might have been, and that lack of success has led to two of the hallmarks of the current Bike 4.0 era: an upswing in direct-to-consumer sales, whether done on a Click & Collect basis or by cutting the dealer out of the process entirely, and the outright purchase of entire chains of bike shops by three of the four Quadrumvirate brands, with Trek leading the charge.

Oversupply accelerates the race to the bottom

This kind of scorched-earth thinking hasn’t worked for the last twenty years, and there’s no reason to think it will work now or in the future.

To be fair, forecasting next year’s bike sales is not a simple process. For one thing, it’s highly weather-dependent. But over-forecasting nine years in a row — not to mention the current inventory quagmire we dragged ourselves into post-covid — should send the message that we just don’t need to be bringing in quite so much product every year.

Among many other issues, continuous oversupply combined with in-season discounting has conditioned consumers not to buy their bikes until the discounts kick in. And who do we have to blame for this? No one but ourselves. We as an industry have literally trained the expectation of season-long discounts into our customers. And the result has been lower margins for retailers and suppliers alike. All season long.

Not only have we trained consumers to expect in-season discounts, we as an industry have trained ourselves to the oversupply model, and with it the belief that shoving a few more units through the supply chain equals brand success. And that’s because bike brands measure success in number units shipped to dealers, not in ROI.

This kind of scorched-earth thinking is so Bike 3.0. It hasn’t worked for the past twenty years, and there’s no reason to think it will work now or in the future.

Nowadays the whole pre-season ordering process (for retailers anyway) is shambolic. Dealer showrooms are already so crowded with product that they’re simply refusing new shipments. And the growing number of company-owned stores (several hundred prime locations, according to current estimates) has rendered the whole inventory-loading process irrelevant: company-owned shops carry whatever inventory the company tells them to. Meanwhile, forced obsolescence based on model years doesn’t have the clout it once did when dealers are already choking on record quantities of inventory.

So what should we do about this as we enter the 4.0 era? Two things, if they weren’t already obvious. First, get rid of model years, at least on bikes below $1,500. That will prevent inventory from obsolescing, even if you keep it over a season. Spec changes? No problem. Call it a model refresh, couple it with new paint and graphics and mix the newcomers in with existing inventory.

And that second thing? Stop making so darn many bikes. C’mon, guys. Sell slightly fewer units each year at significantly better margins and take home more profit at the end of the year, both for yourselves and your dealers. It will take consumers a few seasons to adjust to the new reality, but in the long run it will be healthy for the industry and ensure better choices for consumers as brands reinvest profits in the development of truly new and innovative products.

If the intent behind Bike 4.0 is for one or two brands to finally overcome the grip of Perfect Competition and achieve higher profitability, it can’t be done by wallowing in the gutter of oversupply and evergreen discounts. As the head of one Quadrumvirate company once told me, “Every challenge is an opportunity.” Well, these are challenging times. And the opportunity right now is to move beyond Bike 3.0’s scorched-earth thinking and look to a more profitable Bike 4.0 future.

There’s a time for industry-leading brands to step up and start acting like actual leaders. And that time is now.