TAICHUNG, Taiwan (BRAIN) — By now, most BRAIN readers have heard stories about extended delivery times for bikes and components from Asia. What's been less obvious is how those delays are harming some of the industry's smaller and newer brands.

In recent decades it's become remarkably easy for entrepreneurs with an idea to bring it to market quickly with the help of Taiwan's remarkable bike-making infrastructure. They can jump on new product trends, place small, just-in-time orders, keep inventory minimal and stay a step ahead of the giant multi-national brands.

Often they work closely with their factories, providing non-binding forecasts that get turned into orders with delivery in 45 to 60 days. The most successful build trust with factories over years and decades, showing that their forecasts are reliable and they pay their bills. The entrepreneurs might lack the resources to forecast 18 months out or make a huge order, but they can establish a profitable business relationship.

This applies whether the entrepreneur is enlisting Taiwan factories to make a simple component or a complete bike. And in some product categories, the impacts discussed in this article apply to those having products made in China or elsewhere in Asia and Southeast Asia, as well as Taiwan.

"All hell broke loose"

The nimbleness these brands enjoy put them at risk when the bike boom went off in early 2020. Once the industry realized demand was spiking, the biggest brands quickly flooded factories with orders.

"By about May, all hell broke loose," said Aaron Abrams, Marin Bike's Taiwan-based product director. "The big guys were placing orders with everybody, for everything. They would place multiple orders and see who delivered first."

Remember those non-binding forecasts from the small brands? They went out the window.

"The big guys were placing orders with everybody, for everything"

The factories, most of them, accepted orders on a first-come, first-served basis. And, you've heard about it: Lead times went from the typical 45 to 60 days to 300 days, then 350, 450, or even 540 days.

All companies get quoted those kinds of lead times now for a new order. What's different for the smaller brands is that many got bumped out of the queue in the early days, and now, if they can place an order, they won't get product for a year. Their cash flow disappears, as does their quick-to-market advantage.

"If you are a brand that needs to keep turning small orders and now you can't get enough product to pay the bills, well, depending on how long your runway is, that could be the end," said Abrams.

Opportunities lost

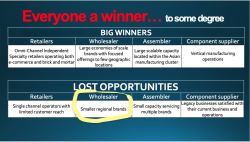

At a presentation in Taiwan last week, Specialized's Bob Margevicius showed a slide of industry segments that missed opportunities from the bike boom.

He said online-only brands left money on the table because they lacked the pipeline of inventory held by traditional bike shops and their suppliers (he said the IBD channel had 8 months of inventory in stock at the start of the boom. It's unlikely any e-commerce brand had that buffer).

"Legacy" component makers — those that make complicated parts requiring big capital investments, like derailleurs and suspension — missed growth opportunities because they couldn't expand capacity quickly, Margevicius said.

And finally, he said, small brands and small bike assemblers missed the opportunity to make huge profits during the bike boom — because they often simply had nothing to sell.

"A lot of the small brands have a really hard time getting components," Margevicius said.

An early decision

According to an August 2020 article by Larry Kanter on Marker, a Medium.com site, Trek, led by its president, John Burke, was one of the first brands to realize the boom was going off and started placing huge orders with suppliers, including Shimano, last April.

"Yutaka Taniyama, vice president of sales of bicycle components at Shimano ... heard from Trek in April," Kanter wrote.

"It had been a punishing few months for Taniyama, with order after order being canceled from manufacturers around the world. "I would call it a storm," he says. "A panic." And then the Trek rep came calling.

Taniyama could not believe what he was hearing, and reached out to Burke to clarify. "John explained what he had seen and showed me the data that showed that the forecast needed to increase," Taniyama says.

So Shimano, which operates on a first-come, first-served basis with its clients, took its excess capacity and directed it to Trek. "They made a decision early," Taniyama says. "Now, everyone else is following."

Hoarders and allocators

Are the big brands hogging production capacity, over-ordering to push out competitors' lead times or even hoarding product in secret warehouses?

Few sources in the industry want to talk about it directly. In nearly two dozen interviews researching the supply chain, most sources chuckled when asked about it.

"I left my conspiracy hat at home today," said Joe Graney, the CEO of Santa Cruz bikes.

Some just smiled and shook their heads, the non-verbal communication that makes a Zoom interview worthwhile.

Industry consultant Jay Townley said brands are doing what they need to do.

"At this point it appears that the big brands are doing their utmost to control as much capacity as they can afford," Townley allowed.

On the other side of the coin, do suppliers allocate their production, doling it out in some sort of equitable manner rather than just in the order of orders received?

Yes and no. Larger brands typically set aside a certain amount of production for aftermarket vs. OE, although in a pandemic boom year, the OE orders usually get first priority. Some have small-builder programs and more formal geographic allocations.

But some allocations happen after the product leaves its factory and is being handled by a trading company or a bike assembly factory.

The big bike brands have leverage because only big brands use the biggest bike assembly factories. Those factories might only have 10 clients. Ten big clients. While the bike brands communicate directly with the component makers, their OE orders are often made through the assembly factory. And when a big assembly factory bundles a bunch of big orders into one REALLY big component order ... well, the big get bigger.

Believe in the bike

On the other hand, it's not always the biggest who come out on top. Kona Bikes, the epitome of a medium-sized brand, has been working with one of its bike factories in Taiwan since 1988, said Jacob Heilbron, Kona's co-founder.

On the other hand, it's not always the biggest who come out on top. Kona Bikes, the epitome of a medium-sized brand, has been working with one of its bike factories in Taiwan since 1988, said Jacob Heilbron, Kona's co-founder.

Kona has been able to keep bikes flowing, which Heilbron attributes to two things: trust and the company's "belief in the bike."

"We've built up a large level of trust" with suppliers over the years, Heilbron said.

It also helped that Kona didn't blink in the first scary days of the pandemic when many were canceling orders.

"We never canceled orders: we believed in the bike," he said. "It's easy to say in hindsight, but we've seen that whenever there is a natural disaster — and that's what this pandemic is — bike sales go up. Bikes are just such great solutions. So we kept our orders in and our retailers are giving us good marks for delivering more than they expected. Hopefully we can maintain that; our goal is to increase market share."

And others attribute their ability to keep a steady supply of components to simple persistence.

"The one that talks the loudest gets the stock," said Martin Le Sauteur, the CEO of Montréal's Argon 18 bike brand. "We have to play elbows. If you just accept it, they will take advantage of you," he said.

Call it cooperation

The Taiwan industry is a small world. Many business owners have family and/or investment ties with other companies. The owner of a bike assembly factory might have a brother who owns a fork factory, or might have an investment in a brake supplier.

So it's not surprising when a small amount of allocation — call it what you will — takes place, sometimes to the bafflement of Western buyers.

"There is this level of cooperation there even among competitors that is foreign, I think, to the American capitalist way of doing things," said Steve Gluckman, who ran REI's bike business for years and is now an industry consultant.

"There is this level of cooperation there even among competitors that is foreign, I think, to the American capitalist way of doing things," said Steve Gluckman, who ran REI's bike business for years and is now an industry consultant.

Ann Chen, marketing manager for Taichung's Velo saddle company, echoed Gluckman's term: Cooperation.

"Velo has always tried our best to service our customers' needs," Chen said in an email to BRAIN.

Velo dominates the OE market for quality saddles. Customers told BRAIN there are few viable alternatives. And they said Velo currently has lead times of well over 300 days.

"There is no doubt that (our) lead time is long now," Chen said. "As for how long, it really depends on the product line and the processes that a product has to go through. I hope and I believe that Velo shouldn't be the worst one, though."

Asked if Velo allocates production, she said, "Of course, for some customers who don't always buy from Velo and/or have less cooperation in past years (it) will be difficult to get a good lead time in Velo. I believe this problem is not about the size of the customer but our coordination habits."

Fall out

Few can point to examples of any brands that have closed because of factory lead times. Young, small brands have an ability to quietly fade away, or at least step back to re-tool. Thesis, launched in 2018, is one small brand that radically changed its model because of the pandemic.

The brand originally allowed D2C customers to customize their bikes' specs, choosing components and wheel and tire size. The bikes were assembled in Taiwan and drop-shipped to end-users in the U.S. But with the increased lead times for components, Jacobs decided Thesis had to stop offering complete bikes.

"It required a shift in strategy for us," said Jacobs, who worked in Taiwan doing product development and sourcing for Specialized before launching his own company. "We're fortunate that our business is very lightweight and flexible so we can scale up and down and adapt."

Fit 5, a new brand that launched a multi-platform indoor cycling pedal last fall sold out its first production run. It then ran into lead times so long that the company temporarily halted marketing and sales efforts, partner Steve Cuomo told BRAIN.

And other brands continue on with tightened margins and more headaches.

Bunch Bikes, a cargo bike brand launched in 2017, has had cash flow challenges due to component lead times, said founder Aaron Powell.

"We have continued to put down deposits on production runs for our cargo bikes 10 months in advance since last summer," he said in an email to BRAIN. "We are right now in the process of putting down deposits for components for the first half of 2022, based on a forecasted rate of growth on a forecasted number of 2021 sales (i.e. we're guessing!)

"Some components saw such a rapid increase in lead time recently that we completely missed the boat for 2022 and are now having to test possible substitutions. Anything to avoid going out of stock next year.

"The cash flow challenges are serious, but thankfully we've been able to stay on top of it so far through federal loans, investors, and a line of credit," he said.

Small U.S. frame builders can control their own destiny when it comes to their signature product, but some are struggling to get build kits from distributors or their OE suppliers. For many, the current demand is such that they continue to sell frames at a good rate, but they are losing potential complete bike sales.

"I've had to buy parts at retail to finish a bike; what are you going to do?" said Johannes Schmidt, sales and marketing manager for Dean Bikes, a Boulder, Colorado, frame maker. Schmidt said Dean has frame orders booked out for several months.

"I can still secure SRAM builds for people, but Shimano is pretty tough. I tell some people they might be better off sourcing from (UK-based e-commerce sites) Merlin Cycles or Wiggle."

The barrier of entry rises

Industry observers like to roll their eyes at the plethora of new bike brands in recent years. For them, a higher barrier to entry to the industry might be a welcome development. Fewer brands might equal higher prices and higher margins.

But Todd Latta said the industry relies on the small companies that innovate and push technology.

Latta, a Canadian, lives in Taichung and runs a business called Essanty that does product development, light assembly and supply-chain management for a variety of bike brands, including some very small ones (both Thesis and Fit 5, mentioned above, are Essanty clients).

It would be in component factories' best interest to diversify their customer base, he said, so they are not beholden to a small number of powerful customers.

But he said he hasn't seen any factory do that. "We haven't seen anything but first-come, first-served," he said.

It's more than just the long lead times challenging small brands and innovation, he said.

COVID-19 travel restrictions make it hard for innovators to work closely with their factories to supervise production. Not every company can afford to keep a staff in Taiwan or send an employee to quarantine in Taiwan for three weeks.

Travel and communication can feed innovation.

"There's an information gap," Latta said. "The last (in-person) trade show was Taichung Bike Week in 2019. It's hard for people to find new sources and new ideas. I worry about the effect on ingenuity across the industry."

Why not just make more?

After an extended Chinese New Year break in early 2020, many factories were able to return to their normal capacity or more by summer. And faced with the overwhelming demand, most factories added production lines and more shifts. Most observers say Asia is producing as many or more bikes than it ever has; it's just that demand is, at least for a time, higher than it's ever been.

But there are few reports of Asian factories making major capital investments in new production machinery or breaking ground on new factories.

Last week, Specialized's Margevicius, along with the CEO of Accell Group, called on Taiwan component makers to significantly increase capacity. Later this week BRAIN will take a deeper look at manufacturers' plans for increasing capacity.

Related: