WASHINGTON (BRAIN) — President Donald Trump followed through on recent threats and announced increased tariffs on goods from China, Mexico and Canada on Saturday. The new tariffs — and a closure of the de minimis loophole on the three nations — were to take effect at 12:01 am Tuesday, but on Monday Trump said he had negotiated a 30-day delay with Canada and Mexico. The China changes were still set to take effect Tuesday.

The new tariffs are imposed under the authority of a Nixon-reform era law allowing the President to impose sanctions in a time of crisis. Trump cites fentanyl imports and illegal immigration as the crisis justifying the new tariffs, which are:

- 10% additional tariffs on Chinese goods (in addition to existing tariffs, bringing the full tariff on Chinese mountain and kids bikes to 46%, for example);

- 25% on all goods from Canada and Mexico, except for Canadian energy and oil exports, which will be taxed at 10%.

What does it mean?

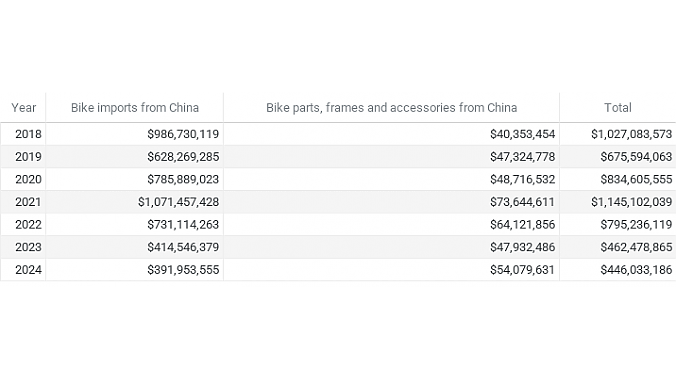

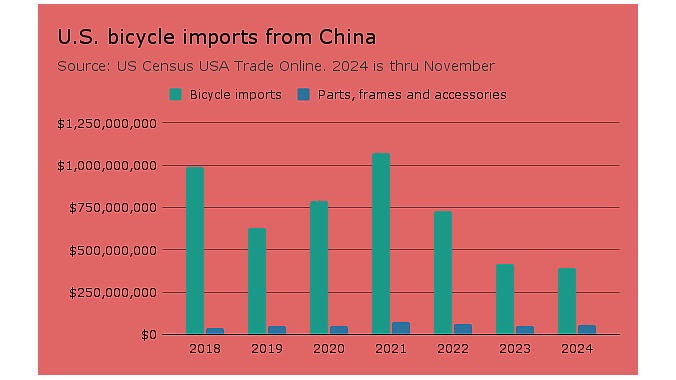

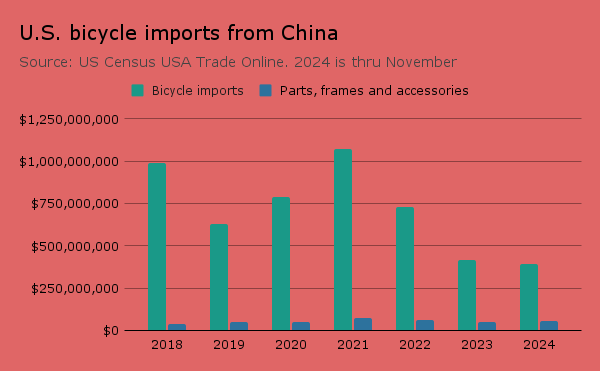

As we’ve reported before, the U.S. gets an estimated 87% of its bicycles from China, in a unit count, but less than 50% of the dollar value of bikes imported is from China. That’s because most Chinese bike imports are very low-cost juvenile bikes bound for the mass market. For complete bikes, the specialty market is much more dependent on Taiwan, and, increasingly, Vietnam and Cambodia.

“The specialty bike industry has moved out of China. Anyone that is still there has only themselves to blame,” one manufacturer told BRAIN on Monday. They said the new tariffs will encourage U.S. bike assembly, just as anti-dumping tariffs in Europe have encouraged new factories to open there in the last decade.

Still, the U.S. industry at large remains dependent on China not just for low-cost kids bikes, but also for some higher-priced carbon frames and components and a lot of softgoods including shoes and helmets. Many of the bikes and e-bikes assembled and finished in other Southeast Asian factories are still using frames and other parts made in China (and many of the factories in Southeast Asia are owned by Chinese companies).

Still, the U.S. industry at large remains dependent on China not just for low-cost kids bikes, but also for some higher-priced carbon frames and components and a lot of softgoods including shoes and helmets. Many of the bikes and e-bikes assembled and finished in other Southeast Asian factories are still using frames and other parts made in China (and many of the factories in Southeast Asia are owned by Chinese companies).

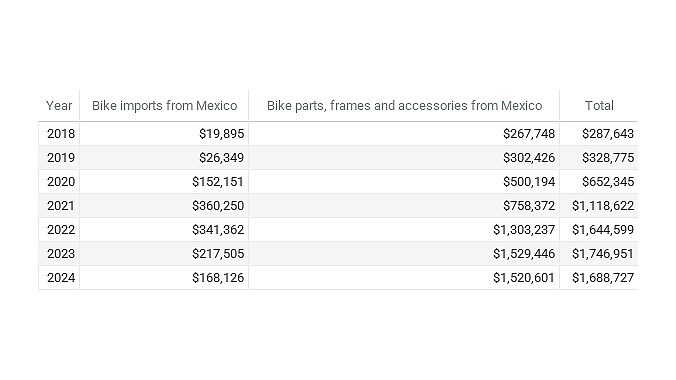

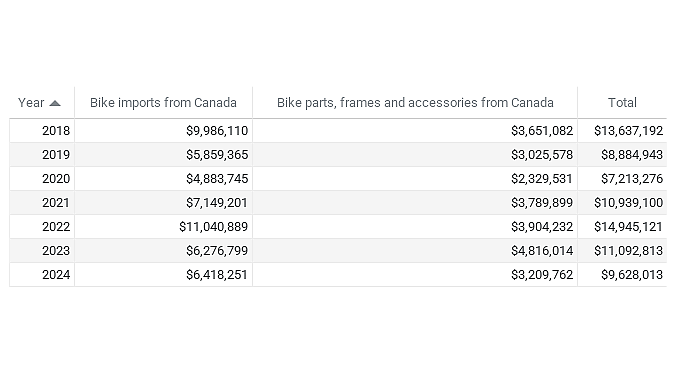

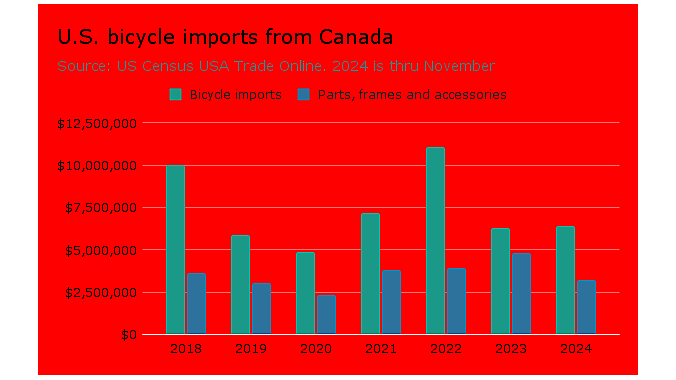

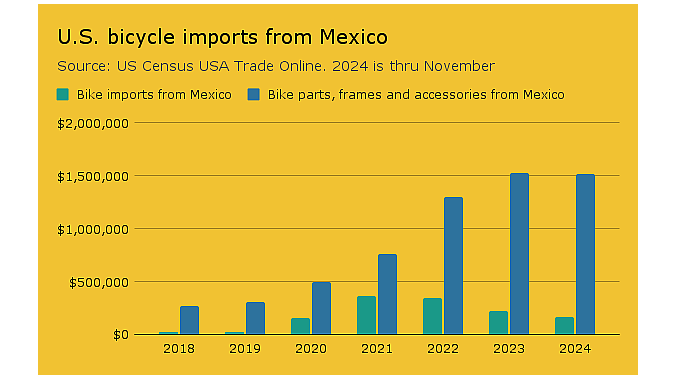

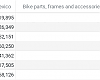

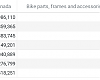

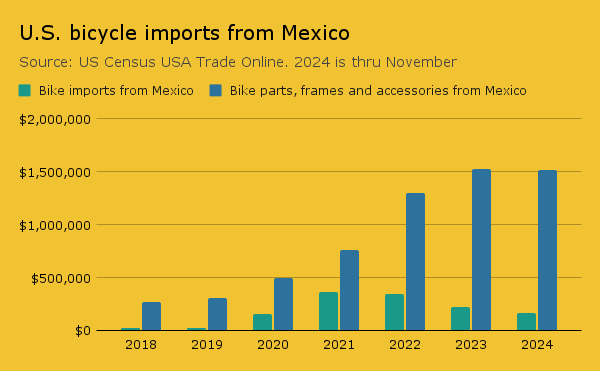

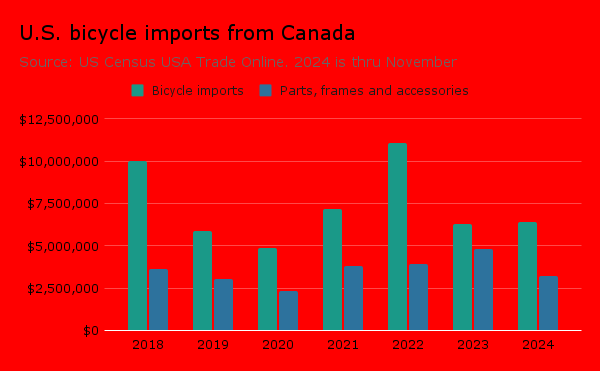

Meanwhile back in North America, the industry imported just $1.7 million in bicycles and bike parts from Mexico in the first 11 months last year, and less than $10 million from Canada over the same period. The figures do not include e-bikes and softgoods including cycling apparel, shoes and helmets. For comparison, by the same measures the U.S. imported $446 million in bike goods from China in the first 11 months.

Mexico a sleeping giant?

Tech and automobile suppliers from China and Taiwan have been rapidly setting up manufacturing clusters in southern Mexico for several years, and there are occasional rumors about major Asian bike makers pursuing a similar route.

Mexico’s proximity and low labor costs, combined with the free trade provisions of NAFTA and its replacement, USMCA, have long been attractive to U.S. brands. But Mexican production has largely been more of a theory than a reality for the U.S. industry.

Spinergy has been making bike and wheelchair wheels in Mexico for years. Yakima made some products in Mexico for years, starting soon after NAFTA became law, but later moved most or all that production to China.

Sinbon, a Taiwanese tech company that, among other things, offers e-bike systems, broke ground on a factory in San Luis Potosí, Mexico, last year. Sinbon will show its e-bike and e-cargo bike systems at the Taipei Cycle show in March.

In 2019, BRAIN’s Marc Sani reported on Mercurio’s new bike factory in Mexico and the company’s plans to sell into the U.S. market. It’s not clear if Mercurio ever succeeded in selling significant quantities in the U.S.

Louis Garneau Sports has operated both south and north of the U.S. borders. The company opened a factory in Mérida, Mexico, in about 2011 that shipped about half its production to the U.S. and half to Canada. After Garneau declared bankruptcy in 2020, the company said the Mexican factory (and Garneau’s U.S. outpost in Vermont) were unaffected. But in early September last year, Louis Garneau Sports was acquired by the Canadian sports apparel brand Lolë. Later that month a protest broke out in Mérida after the Garneau factory there was suddenly closed, according to Mexican news reports. Emails to Louis Garneau Sports and Lolë on Monday were not returned.

Tight ties with Canada

Some Canadian brands and distributors regularly ship products back and forth across the border, a process that has been duty-free until now. The new tariffs may make that more burdensome, even if most of the products are made in Asia or Europe.

Brands in some industries operate distribution centers in Canada that take advantage of the de minimis loophole to ship sub-$800 packages of Chinese products directly to U.S. consumers. To what extent that is happening in the bike industry is unknown. The loophole for Canadian and Mexican products remains open another 30 days.

One supplier told BRAIN that, although shipments from the U.S. into Canada had been duty free, they were sometimes slow. This supplier, whose products are mostly from Europe, has chosen to ship directly from Europe to its Canadian dealers, bypassing the U.S. even before the latest developments. It’s not clear how many other suppliers do the same.

Canada-based Norco operated a U.S. warehouse in Utah as recently as 2023. The company now relies on distributor HLC for sales in the U.S., but continues to use the Utah warehouse.

Eva Wyper, Norco’s brand marketing lead, said, “Today, our supply chain is built on a foundation of innovation, quality, and flexibility. This solid foundation ensures that we can continue to support our growing U.S. dealer network and rider base without disruption, even with the new tariffs the U.S. imposed on Canada.” BRAIN has asked for more details from Norco and has reached out to HLC.

Canada’s Argon 18 manufactures most of its frames in Asia, but assembles bicycles in Montreal for the U.S. market, a company representative said.

Kona Bikes, based in the U.S., has always maintained a Canadian warehouse. "We keep inventory separate for U.S. and Canada, although it’s not clear how cross-border shipments of non-US or Canadian-made goods would be treated," Kona's Jake Heilbron told BRAIN on Monday.

Retaliatory tariffs might be a bigger factor.

Before the 30-day truce was announced Monday, Canada had already announced plans for retaliatory tariffs of 25% on some imports from the U.S. Those imports include bicycle tires and rim strips, an odd inclusion since to our knowledge no bike tires or rim strips are made in the U.S. The retaliatory tariffs are on hold during the 30-day truce.

Like many U.S.-based brands that manufacture overseas, high-end tire brand Rene Herse Cycles ships significant tires from the U.S. to Canada, the company’s Jan Heine told BRAIN. In a letter to customers over the weekend, Heine told Canadian customers to relax.

“The tariff is based on where something is made, not where it is coming from at the last stage of its journey. Rene Herse tires are made in Japan and France, not the U.S.—simply because there is nobody in the U.S. who can make supple high-performance bicycle tires. This means they are not affected by the new tariff, and neither are other Rene Herse products (even those made in the U.S. don’t fall under the new tariffs),” Heine wrote.

Europe next?

Trump is promising that the European Union is next to face punitive tariffs. On Monday he complained that the U.S. is running a trade deficit with the EU on auto and farm products specifically. Any Trump tariffs on the EU would be surely followed by retaliatory tariffs, which could affect sales of U.S.-made bike products sold in Europe. The last time the EU threatened retaliatory tariffs on U.S. products, in 2020, it affected U.S. manufacturers like Allied. The EU tariffs were in place for about seven months and then suspended for five years.

A note on the graphs above: The data does not include e-bikes and some cycling product categories such as apparel, shoes and helmets. The numbers also do not include shipments made under the $800 de minimis threshold.