A version of this article ran in the September issue of Bicycle Retailer & Industry News.

By Alan Coté

Leading bike and accessory companies are increasingly using the U.S. patent system to protect the appearance of their new products. In the U.S., patents come in two flavors: utility patents, and design patents — with the latter gaining popularity as a form of intellectual property in many industries, including our pedal-based one (there is a third type of patent specifically for plants).

A utility patent is what most people think of when patents are discussed. They in general terms protect how an invention works or is used. This includes machines, compositions of matter, articles of manufacture, and processes (including methods). Meanwhile a design patent protects the ornamental appearance of something — that is, the way it looks, not the way it functions. This doesn't mean paint schemes or graphics, but the shape and form of something.

For example: the internal components of a shift lever, shock, headset, etc. and how they work together, could be the subject of a utility patent. The shape and look of a crankset, a bike computer, or even a frame (if distinctive enough) could be covered by a design patent.

It is in recent years that bicycle companies, as in many other industries, have been seeing increased value in protecting their inventions with design patents. Between 2010 and 2020, design patents rose from 5.5% of total U.S. patent applications filed, to 7.4%. A catalyst for this interest has likely been a long-running lawsuit between Apple and Samsung over smartphone technology. After a decade of litigation, in 2018 Apple won over $500 million for Samsung's infringement of three design patents, but only $5 million for infringement of three utility patents.

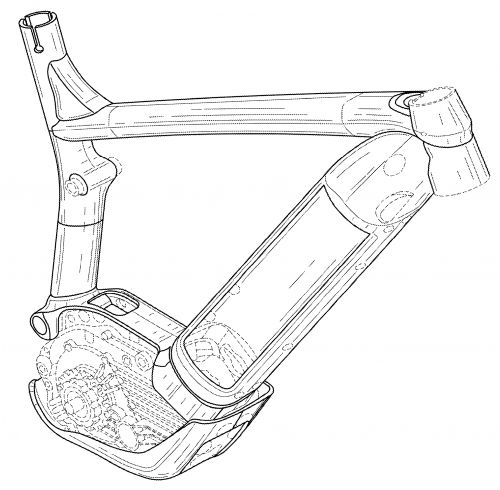

Consider Specialized, a bicycle company that's been showing strong interest in design patents. In 2021, the company was issued 6 design patents and 17 utility patents. This included five different patents claiming the look of different frames. Trek was issued three utility and two design patents in 2021 — one for the front triangle of a full-suspension e-bike frame, another for a cube-shaped light.

Other industry companies with strong design patent portfolios include Garmin, with many covering the appearance of watches, watch straps, watch bezels, and bike computers. Electronics rival Wahoo has had four design patents issue in the last year, covering a watch, heart rate monitor strap, adjustable crank arms, and even the frame of a stationary bike.

Some new products may not be functionally different enough compared to previous products to be granted a utility patent, but may be ripe for a design patent due to a new appearance. An example is brake rotors: in 2022 alone, SRAM has been issued four U.S. design patents for brake rotors. Another example is footwear, with Specialized having a design patent on the flaps that overlap a shoe, in conjunction with dial-fit systems like a Boa. A conventional bicycle frame with a front and rear triangle may be nothing new, but if there's a new tubing curve or tube junction that hasn't been seen before, a design patent can be a tool to stop copycats from creating an identical look.

Another factor in this trend may be that an application for a design patent is much less complicated and far less expensive than that of a utility patent. Additionally, the process of getting the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to issue a utility patent almost always requires extensive, costly, back-and-forth deliberations between a patent examiner and a company's patent agent/attorney, all with much uncertainty as to whether a utility patent will end up being granted. Total cost for a obtaining a design patent might range from 10%-20% of the total cost for a utility patent. The term of a design patent is 15 years, whereas a utility patent is 20 years – but the latter requires thousands of dollars in maintenance fees (paid to the USPTO) over the life of the patent to remain in force.

Consider this in the context of Specialized's design patents for frames: obtaining a utility patent for the junction of a headtube with a downtube and toptube may not be possible at all – and if it was, it likely would require a drawn-out, costly legal process with the USPTO. A design patent, meanwhile, entails much lower costs, and is generally much more likely to be granted.

There may be another strategy behind design patents: selling on Amazon. Enforcing a patent through litigation is a costly move, often totaling several million dollars, and taking years. But Amazon has a robust, in-house program for enforcing intellectual property rights, wherein infringement complaints are received and processed. Sources have told me that Amazon doesn't get too far into the weeds examining the minutia of patent infringement — rather, they often simply remove accused products from seller listings if infringement looks possible. So a design patent may provide a simple, low-cost, rapid way to remove knock-offs from a massive marketplace.

There are several notable exceptions with the trend towards design patents, including Shimano. The company was issued 137 U.S. patents in 2021, with only three of those design patents (all three were for fishing reels, not bicycles). Likewise, Italian rival Campagnolo has barely touched U.S. design patents in recent years, with the most recent in 2019 for a crankset – and prior to that a surprising one for a type font in 2016. Fox Factory had 31 patents issue in 2021, but none were designs. In fact, Fox has had no design patents in at least the last 10 years, though that may reflect its focus on internal suspension technology, rather than more visible products.

Alan Coté is a Registered Patent Agent & principal of Green Mountain Innovations LLC. He's a past contributing writer to Bicycling, Outside, and other magazines, and a former elite-level racer. He also serves as an expert witness in bicycle-related legal cases. Nothing in this article should be considered legal advice, nor does it establish a client relationship.