The following article ran in the November issue of Bicycle Retailer & Industry News.

By Alan Coté

Patents are often mentioned as limiting the release of a new product from more than one manufacturer. Which of course, is exactly how the patent system is intended to work. Does it follow that when a patent expires, the floodgates open and wider product offerings hit the market?

Intellectual property rights come mainly in three types: trademarks, copyrights, and patents. Trademarks are a word, phrase, symbol, or design that identifies goods or services, and can carry on perpetually — there’s no future expiration for the names Coca-Cola, Trek Bicycles, etc., so long as they continue to be used. Copyrights currently have a term of the author’s life plus 70 years (with some variations) — after that, rights are in the public domain. Consider the numerous Sherlock Holmes movies and TV shows in the last decade. The copyrights expired, and the floodgates opened.

Utility patents, meanwhile, have a much shorter life, spanning 20 years from when an application is filed (design patents, which protect ornamental appearance, expire 15 years from the date of grant). When a patent expires, the rights claimed in the patent move into the public domain, meaning anyone is free to make, use, or sell the invention. Pharmaceuticals going “generic” when an underlying patent expires is a good example.

Many, or most, bike-related patents expire without anyone noticing. But for a handful of patents, industry members anxiously await an expiration to bring out their own product. One industry member who worked at Shimano in the 1980s remembers the company waiting “to pounce on those opportunities” when a patent expired.

The classic, transformative example, though almost 40 years old, is the patent on the slant parallelogram derailleur.

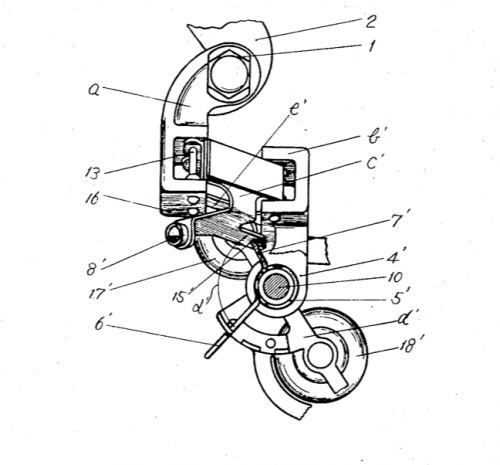

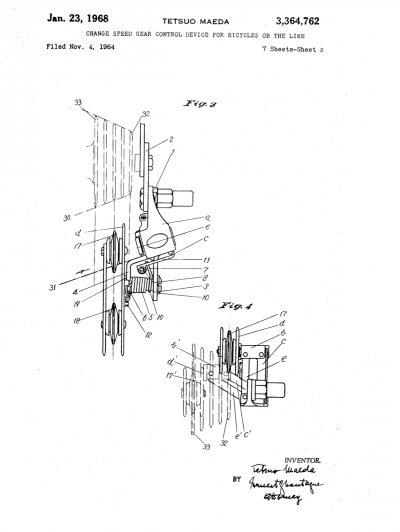

Scroll back, and Japanese component maker Suntour was a major component supplier, reportedly selling twice as many rear derailleurs as Shimano in the early 1980s. One reason: Suntour had patents in various countries that covered a derailleur quite unlike other offerings at the time. The design used an L-shaped derailleur body, with a swinging parallelogram positioned at an angle (the “slant”). This resulted in the pulleys being spaced more closely to each rear cog as the bike shifted. This reduced the amount of “overshift” required at the shift lever, resulting in smoother, more predictable gear changes compared to other derailleur styles.

Scroll back, and Japanese component maker Suntour was a major component supplier, reportedly selling twice as many rear derailleurs as Shimano in the early 1980s. One reason: Suntour had patents in various countries that covered a derailleur quite unlike other offerings at the time. The design used an L-shaped derailleur body, with a swinging parallelogram positioned at an angle (the “slant”). This resulted in the pulleys being spaced more closely to each rear cog as the bike shifted. This reduced the amount of “overshift” required at the shift lever, resulting in smoother, more predictable gear changes compared to other derailleur styles.

Suntour’s patent expired in 1984. Not by coincidence, in 1985 Shimano released an entirely new shifting system, SIS. It included the first commercially successful, high-end indexed shifting system, with the slant parallelogram derailleur design essential to making it work. The advantages of Suntour’s derailleur design were undeniable, and by the end of the decade, Campagnolo and others had also switched to the same design. The same basic slant parallelogram configuration is still used by virtually every rear derailleur today, whether mechanical or electrical.

Clipless pedals are a similar story. French company LOOK created the first successful clipless pedal in 1985, which used the now-ubiquitous three-hole delta pattern for mounting cleats to shoes. Shimano was so interested in the design that they licensed the patent from LOOK for road use, before beginning work on SPD off-road pedals. SPD off-road pedals featured the also-now-ubiquitous two-hole cleat pattern.

“Some pedals avoided Shimano’s SPD patent by using a different mechanism,” said Eric Sampson, who has sold his own line of pedals (and more) for decades through his company Sampson Sports. “But Shimano was really tough on the shoe side — they had a license fee for shoe companies to use the two-hole mounting system.”

Patents surrounding those early clipless pedals are long expired, and now there’s a wide variety of low-cost clipless pedals available from many companies — including those pedals found on gym bikes that have a Look-style mechanism on one side and SPD on the other. Still, a few big companies — mainly Shimano — continue to dominate the clipless pedal market.

Shimano has several patents on rear sprockets, including the Hyperglide patent that was a key part of its indexed system. Several of those patents have expired in the last 10 years, allowing other brands to offer lower-priced cassettes with shifting performance similar to Shimano cassettes. It’s likely that major brands like SRAM have incorporated aspects of the expired Hyperglide technology in their cassettes as well.

More recently, DT Swiss’s 1994 patent on a ratchet freehub — acquired when DT Swiss bought the Hügi hub company — expired in 2015, opening the door for a few other companies to bring out similar designs. On a similar time frame, Cal Phillips’ 1995 patent on a two-arm bike rack was key to the growth of 1Up USA, which he founded. The patent expired in 2015 and Phillips, who left 1Up and founded a new rack company, QuikRStuff, in 2020, has several newer patents on racks. Meanwhile most other major brands have added two-arm racks to their model lines in the last few years.

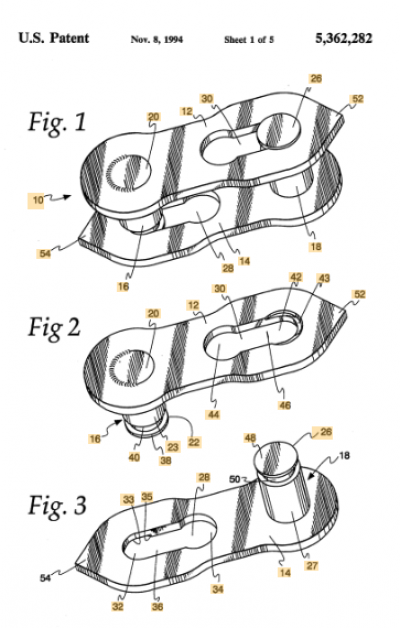

Chicago-area retailer Robert Lickton obtained a 1993 patent on a reusable master link for multi-speed chains, which he sold for years as the SuperLink. The patent expired in 2013 and made it easier for chain manufacturers to bring out their own version of a reusable design.

Chicago-area retailer Robert Lickton obtained a 1993 patent on a reusable master link for multi-speed chains, which he sold for years as the SuperLink. The patent expired in 2013 and made it easier for chain manufacturers to bring out their own version of a reusable design.

There are other examples, but firmly identifying them isn’t easy to do. A delicate legal matter such as patent infringement is not a topic that companies will say much — if anything — about. There’s also the matter that patents are held on a country-by-country basis, with enforcement also at the national level. Meaning, if a company has a patent in the U.S. only, others are free to sell the invention in other countries. So a bike or components may not be offered for sale in all countries, in order to avoid patent infringement.

The “Horst link” rear suspension design, for example, was available on some bikes sold in Europe for years before the patent (owned by Specialized) expired, allowing the import of those bikes to the U.S.

In researching this story, I reached out to a number of industry colleagues, asking for on or off-the-record comments about the significance of expiring patents. They all told similar a story: while it does happen, it’s extremely rare for an expiring patent to open a floodgate of similar products from competitors.

One reason can be product complexity. Consider the threadless headset patent (which I’ve written about in a previous column). Cane Creek (in its earlier incarnation as Dia Compe USA) controlled the market for threadless headsets until the patent expired in 2010 — and not much happened in the marketplace. “For sure there were new players in the headset market, “ said Cane Creek’s director of distributor sales, Peter Gilbert. “But there was no big increase in product offerings — I believe that this was due to the variations of types (fits) of the headset exploded to a significant number as the patent expired.” Now, 12 years later, threadless headsets are available from many companies, although neither Shimano nor SRAM has dipped into that market.

Indeed, manufacturability may often be a bigger concern than patent rights. Take shift levers — which are among the most complex parts on a bicycle. “There are lots of expired shifter patents out there,” said Kevin Wesling, SRAM’s global director of advanced development. “But shifters are really, really hard to build.” Moreover, producing complicated, 20-plus-year-old designs simply isn’t that appealing – like the early Shimano and Campagnolo mechanical shifters, in an age of electronic shifting. “After the 20-year life of a patent, many designs are obsolete,” said Wesling. “The industry has moved on.”

The vast majority of expiring patents go unnoticed. But once in a great while, there’s an invention or design so key that companies are waiting to jump in with their own versions and shake up the bike industry when the intellectual property fences come down.

Alan Coté is a Registered Patent Agent & principal of Green Mountain Innovations LLC. He's a past contributing writer to Bicycling, Outside, and other magazines, and a former elite-level racer. He also serves as an expert witness in bicycle-related legal cases. Nothing in this article should be considered legal advice, nor does it establish a client relationship.