EUGENE, Ore. (BRAIN) — The word you hear most often when you ask Oregon retailers about the state's new bike tax is "hope."

But not "hope" in a very ... hopeful way. Hope in a somewhat dubious way, like when you say, "I hope it doesn't rain on our ride" as you are stuffing a shell into your jersey pocket.

Retailers hope that proceeds from the $15 per bike tax — which they began collecting this week — will be used to improve bike infrastructure as required by the law that created it. Even though almost all retailers BRAIN spoke with this week said they opposed the tax as unfair and misguided, most said if it leads to better bike riding conditions they will feel better about collecting it.

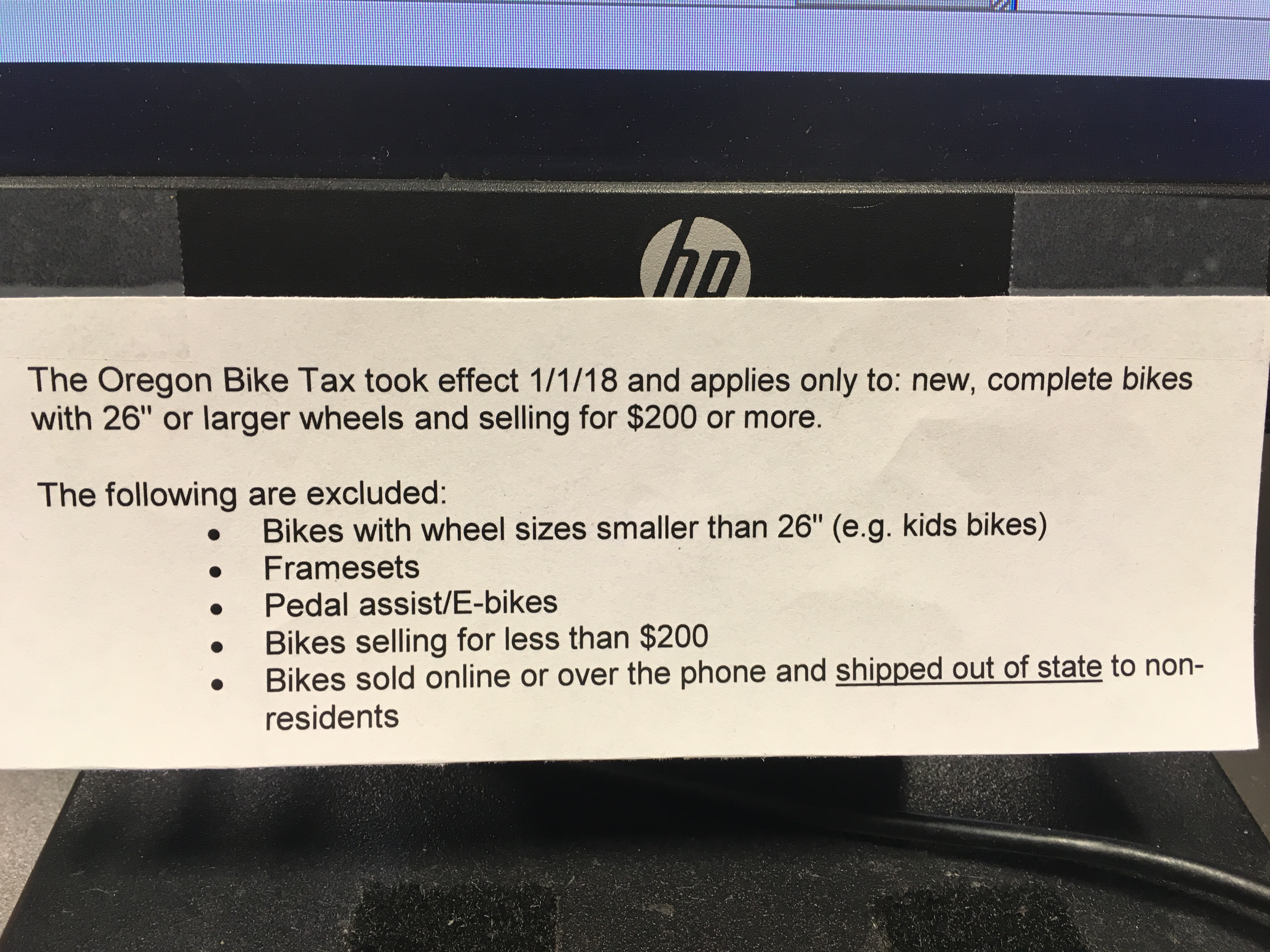

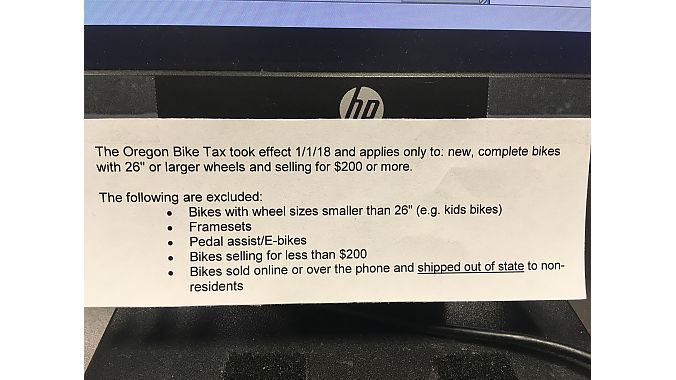

The tax applies to sales of new bikes with 26-inch or larger wheels and a retail price of $200 or more, and is expected to raise about $1.2 million in its first year. Oregon has no regular sales tax, so many bike retailers are unaccustomed to collecting one.

Sprucing up the paths

"I hope it will get used to spruce up the bike paths," said Al Snell, owner of Oregon City Classic Bikes.

When BRAIN spoke with Snell on Wednesday, he had yet to make a bike sale this month, so he wasn't sure how consumers will react. He said he opposed the tax when he heard about it last year and he contacted his state representative to complain.

"Here we are, trying to promote the safest, greenest, easiest way to get around, and you are going to tax us for it?" he asked.

A burden on retailers?

Retailers BRAIN spoke with this week have been more concerned about the fairness of the law, rather than the actual burden or potential effect on sales. But the burden is not inconsequential.

At Bicycle Way of Life in Eugene, managing partner Matt Ritzow estimated that each bike sale in the first two working days of 2018 included an extra 5 minutes of chatter about the new tax. "About half (of the bike buyers) asked if we would just cover it," he said.

He's had to explain that the store can't afford to cover the cost, especially on lower priced bikes. "We've tried to explain that on an average $600 bike sale, by the time we pay rent and salaries and other costs, we make maybe 10 percent. So we end up with $60 and they want us to give away $15 of that. Most people get it once I explain that," Ritzow said.

While the store isn't going to eat the bike tax cost, Ritzow is running an ad in the local weekly paper with a $15 coupon that can be applied to taxable bikes bought this month. "Maybe that will bring some people in," he said.

Ritzow said his POS system requires cashiers to add the tax as an additional line item, a process that would be easy for staff to forget. So he's covered the cash register with sticky notes reminding cashiers of the tax. He's also planning to make a laminated sign to put on the counter to remind customers of the tax.

Like Snell, Ritzow is opposed to the tax because it penalizes an activity that is beneficial — "It's not like we are selling cigarettes, this is something that could actually save money (for the government)," he said — and worries that it could be increased in coming years.

"At some point if the tax gets larger, it will start to have a meaningful impact on bike sales. It's not like we need to give people another reason to buy from Competitive Cyclist or Canyon."

Western Bike Works, which operates brick-and-mortar locations in Portland in addition to an e-commerce business, is paying the tax for its customers.

"We've decided to eat the tax ourselves," said the retailer's Gary Wallesen in an email to BRAIN. "I believe most shops are doing this in Portland. We talked about this tax with our elected officials and told them that shops will use it as a competitive advantage. I just hope the money really goes to helping make the roads safer."

'Pretty wacky'

Bill Larson, the owner of Cycle Path in Portland, said the $15 tax will have little impact on sales at his shop, where the average bike sale is over $6,000. But Larson still opposes the tax.

"The whole premise is pretty wacky," he said. "The $200 minimum is crappy because it takes Walmart out of the mix, so it's not doing the small businesses any favors in that sense. It's just stupid and messed up from the beginning," he said.

Larson is dubious — but hopeful — about the promised infrastructure improvements. "Hopefully after they pay the expenses of putting this into affect, there will be a little left over to actually do something, not just penalize us."

At Sellwood Cycle in Portland, owner Erik Tonkin said he was not opposed to a bike tax, but thinks this tax could have been implemented better.

Tonkin also said the tax hasn't been a burden in the first few days of the year.

"We have sold a few bikes. In general, people seem to be aware of it and — if not — take it in stride. One buyer was very happy about the tax. She was excited to contribute money for programs specifically earmarked for bike infrastructure," Tonkin said.

Unlike other retailers BRAIN spoke with, Tonkin said his store's POS system (from AimSi) dealt with the tax seamlessly.

"Every new bike SKU that falls under the tax protocol now has an automated pop-up attached that adds the tax to the sales invoice. It works well. In fact, it even allows for an 'opt-out' function in case the buyer is tax-exempt."

Tonkin did point out that the retailer will bear the burden of the credit and debit card fee for the extra $15 purchase.

"That adds up when my shop is selling 1,000 bikes per year with an extra $15 attached to each — that $15,000 generates a lot more in fees," he said. In that scenario, a shop would pay $375 a year to process the tax under a typical 2.5 percent card fee.

The new tax was included in a $5.3 billion state transportation bill that passed the Democratic controlled legislature last year and was signed by Gov. Kate Brown, also a Democrat.

Oregon has a short legislative session in 2018 and is unlikely to adjust the law, noted Alex Logemann, the director of state & local policy for PeopleForBikes. He said he had heard of no serious efforts to modify the bike tax in the coming session. So far, other state lawmakers have not taken inspiration from Oregon's tax, said Logemann. A Colorado lawmaker raised the issue on social media last year, but quickly dropped it.