There is nothing the media likes better than a dead cyclist. Unless it’s a dead cyclist who was not wearing a helmet. That salacious and often completely irrelevant bit is invariably tossed in as a lagniappe—a little (bloodstained) bonus—in every report involving the death of a cyclist.

Here’s how it works: “The cyclist, who was not wearing a helmet…” implies not only that a helmet would have saved the cyclist’s life, but that the cyclist was therefore somehow culpable in their own death. The rider in question could have been struck by a drunk driver, flattened by a runaway train, or obliterated by a falling comet. It doesn’t matter. If the cyclist is not wearing a helmet, their death is no one’s fault but their own.

The opposite line—“the cyclist, who was wearing a helmet…”—works almost as well. It implies the danger of riding a bike is so enormous that even a talisman as powerful as a helmet failed to work its magic. Again, the drunk driver/locomotive/comet possibilities are irrelevant.

You’ll also note the headline is, inevitably, “Cyclist Killed,” and never “Driver Kills Cyclist.” Often the driver isn’t even mentioned in the headline. If it bleeds, it leads. And if the thing doing the bleeding was on two wheels when the bleeding started, it leads even better.

Now figure in what politicians like to call the drip, drip, drip factor (the line comes from an old Rolaids ad). Google News articles tagged with “Cyclist killed” average three to five a week, every week, which is to say, a couple hundred times per year. That’s hundreds of times the cycling = death message is shown to millions of Americans each year where the bottom line—what we in the marketing biz call the takeaway—is that riding bikes is pretty likely to kill you. Drip, drip, drip.

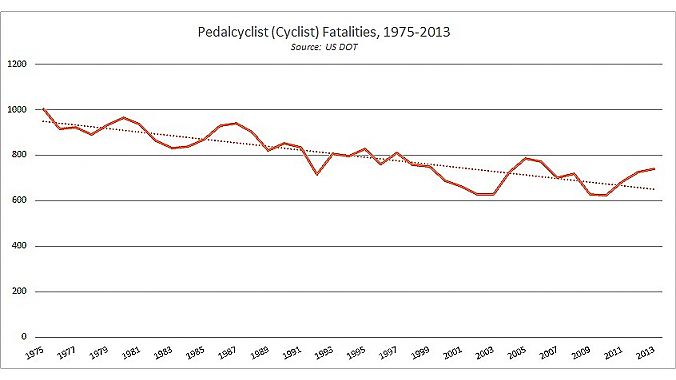

Never mind that Department of Transportation fatality stats show the number of cycling fatalities per year has declined about 30 percent over the past 40 years. Or, that, although the number of cycling fatalities fluctuates from year to year, overall results have remained more or less steady since 2000.

Never mind that Department of Transportation fatality stats show the number of cycling fatalities per year has declined about 30 percent over the past 40 years. Or, that, although the number of cycling fatalities fluctuates from year to year, overall results have remained more or less steady since 2000.

The constant and overwhelming media message is simple: Every trip by bike is a potential trip to the graveyard. Of course, that’s nonsense, and a review of the actual figures exposes that media-induced hysteria for the cynical fraud it is. But who cares? Via consistent (drip) repetition (drip) over time (drip), that cycling = death message has become engrained in the public perception. And in the business of marketing, the business of public relations, the business that sets the national agenda about how people spend their time and money, that perception has already become reality.

Here’s just one example:

“Bicycle Traffic Deaths Soar; California Leads Nation,” screams the Los Angeles Times headline from Oct. 27, 2014. The lead includes the gleefully macabre fact that “between 2010 and 2012, U.S. bicyclist deaths increased by 16%.”

Odd thing is, the 2012 stat is macabre only in relation to 2010, which had the lowest number of cycling fatalities ever recorded. (Of course, the 2010 figure isn’t even mentioned.) In fact, during the 37 years since 1975, 2012 was the 11th safest, with 726 cyclist fatalities, or about 10 percent fewer deaths than the 40-year average of approximately 800.

However, the point is not about what number of dead cyclists is acceptable (at the risk of being obvious, the acceptable number is zero). The point is that diverting public conversation from road safety to an indictment of the dangers of cycling gives the anti-bike crowd a free pass on matters of driver responsibility and the necessity for maintaining safe riding infrastructure. More and more, the cycling = death mantra has become a literal get-out-of-jail-free card for drunk, distracted, and malicious drivers, as well as a convenient excuse for anti-advocacy groups to do nothing at all about it.

The problem is not bikes. It’s not cycling. The problem is that bikes and cycling are being unfairly characterized as a deadly pastime. And that, by doing nothing to stop it, we’ve allowed that demonization to happen.

Next time: Selling Cycling in a Culture of Fear